The Hyakumantō Darani, also known as Dharani in a Million Pagodas, ranks among the earliest securely dated printed works in Japan, completed circa 770 under Empress Shōtoku. Each text—an incantatory Buddhist dharani from the Sutra of the Immaculate Light—was woodblock-printed on a narrow strip of mulberry paper, then rolled and sealed within a miniature three-storied wooden pagoda. In an edition of staggering ambition—one million pagodas—these printed prayers were distributed to the leading temples of the Nara capital.

The project interlaces Buddhist ritual, imperial ideology, and technological innovation, and remains one of the best-documented early printing enterprises in East Asia.

Historical Setting: Court Religion, Crisis, and Imperial Patronage

Empress Shōtoku (718–770) inherited from her parents—Emperor Shōmu and Empress Kōmyō—a vision of Buddhism as an armature of the state. Shōmu had sponsored the Tōdaiji Great Buddha (Vairocana), a colossal affirmation of Buddhist kingship; Kōmyō oversaw large-scale scriptural copying and temple patronage.

Shōtoku’s second accession followed the suppression of the 764 rebellion led by Fujiwara no Nakamaro. In this fraught aftermath, she turned to Buddhist ritual on an imperial scale, commissioning one million miniature pagodas each enshrining a printed dharani, a gesture that sought to stabilize the realm, accrue merit, and broadcast righteous rule.

Text and Ritual: The Sutra of the Immaculate Light

The dharani come from the Mukujōkō darani kyō (Raśmivimalaviśuddhaprabhā-dhāraṇī-sūtra), a short but potent text translated into Chinese in the late seventh to early eighth century. It sets forth six dharani and prescribes rituals centered on the construction, repair, and veneration of pagodas, promising purification of sins, prolongation of life, protection of the ruler, and cosmic order.

In Shōtoku’s project, four dharani were selected and printed—the Konpon (Root), Sōrin (Pagoda Finial), Jishinin (Aspectless Self), and Rokudō (Six Perfections)—with the Sōrin text supplying the conceptual engine for multiplying small pagodas as penitential and protective offerings. The sutra’s instructions to produce numerous small pagodas containing copied spells provided scriptural warrant; the choice of “a million” resonates with both ritual numerology and Kegon (Huayan) cosmology in which multiplicity figures the presence of the Absolute Buddha.

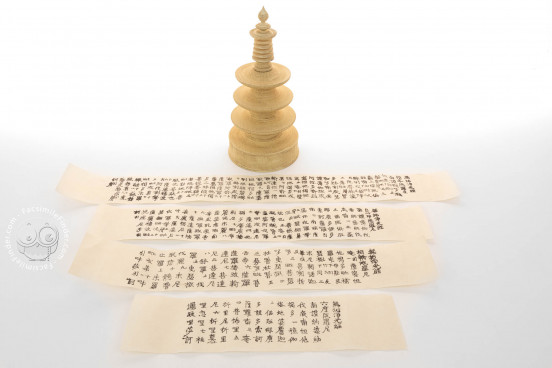

Material Form: Miniature Architecture and Printed Scrolls

The pagodas are miniature marvels. Typically about 21 centimeters tall, they were turned on a lathe from hinoki cypress (bases often in cypress, bodies sometimes in katsura), with a three-storied form and a seven-ringed finial. A cylindrical cavity bored into the body held the rolled paper. Many were primed with white lead and painted; some bear faint ink inscriptions on the base with dates or production notes.

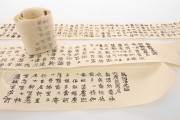

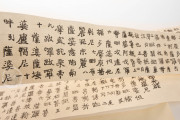

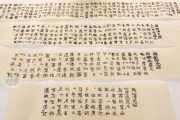

The printed slips—buff mulberry paper strips several centimeters wide—carry neatly rendered columns of Sino-Japanese characters, often with intralinear glosses, and begin with titles identifying the sutra and the specific dharani. The physical act of opening the pagoda, extracting the scroll, and chanting the dharani created an intimate devotional moment embedded within a vast collective offering.

Printing Technology: Process, Scale, and Debate

The Hyakumantō Darani constitutes one of the earliest firmly dated examples of printing in Japan, documented in the Shoku Nihongi (797) and elaborated in the Tōdaiji Yōroku (1106). Although the chronicle notices do not explicitly spell out the method, the Tōdaiji record describes the contents as printed and lists 157 officials and artisans rewarded upon completion in 770.

The scale required 250,000 impressions of each of the four dharani texts. Scholarly study of surviving exemplars suggests that for each dharani two “master” versions were used (often described as long and short), likely to accommodate production in separate studios in the Left and Right Capitals of Nara, perhaps at Tōdaiji (East) and Saidaiji (West).

The impressions are relief prints. Whether the masters were woodblocks or cast bronze plates remains debated. The consistent sharpness across large runs, with little evidence of woodblock fatigue, has led many to posit bronze plates cast from durable clay matrices via lost-wax methods—technologies well established in eighth-century Japanese metalworking. Inks were brushed and impressions likely taken by rubbing, yielding crisp, dark characters despite the small format. Whatever the exact technique, the enterprise showcases a sophisticated command of materials, labor organization, and reproducible text technology in the Nara period.

Political Theology: Merit, Order, and Authority

The Hyakumantō Darani must be read as political theology in action. The sutra promises purification, longevity, and the protection of a righteous monarch; the multiplication of pagodas transposes private piety into public policy. The number one million mapped a cosmic geometry onto the archipelago, magnifying an imperial vow into countless identical offerings. The project thus complemented the earlier ideological statement of the Tōdaiji Great Buddha: where the Daibutsu concentrated sacral kingship in a single monumental image, the Hyakumantō dispersed it through a million micro-shrines, each enfolding dharma, merit, and imperial patronage.

Use and Afterlife: Distribution, Devotion, and Disappearance

Upon completion, sets of 100,000 pagodas were apportioned to ten major temples of the capital region, including Tōdaiji, Hōryūji, Kōfukuji, Yakushiji, Daianji, Saidaiji, Gangōji, Shitennōji, Gufukuji, and Sūfukuji. Housed in dedicated halls (shōtōin), the pagodas served as objects of veneration for monks and lay visitors who could open them, unroll the slip, and chant the dharani at ritually charged hours of the day.

Over the centuries, most sets were dispersed or lost. Hōryūji maintained the largest surviving corpus into the modern era; an early twentieth-century survey counted tens of thousands of pagodas but far fewer intact scrolls. Today examples are preserved at Hōryūji and in collections worldwide, such as the Scheide Library’s finely printed Sōrin darani and its accompanying pagoda.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Hyakumantō Darani": Hyakumanto Darani facsimile edition, published by Maruzen-Yushodo Co. Ltd., 1997

Request Info / Price