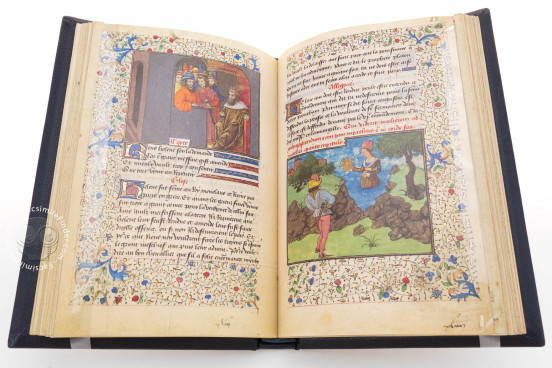

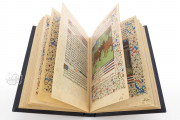

Written and illuminated in France in the 1460s, with miniatures by the Piccolomini Master and his workshop, the Hague Epistle of Othéa is an illuminated copy of a moralizing text by Christine de Pizan, a series of 100 short poems about a person or event from ancient mythology. These poems form a lengthy letter from Othéa, the goddess of Prudence, to Hector, the Trojan prince who is a central character in Homer's epic Greek poem Iliad. Each chapter is introduced by a large miniature on a page with a decorated border.

Created more than half a century after Christine composed the text, the manuscript is thought to have been copied from one made during her lifetime, which featured an equally extensive picture cycle.

A Distinctive Figure Style

The illuminator who painted the first miniature (fol. 2r) is named the Piccolomini Master after his work in a manuscript of two literary works by Enea Silvio Piccolomini, later Pope Pius II (Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, MS 68). In the Hague manuscript, he supervised several other painters, all of whom worked in close collaboration.

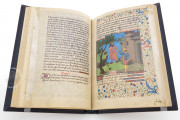

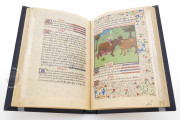

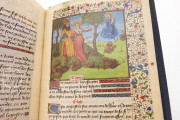

Despite the participation of many artists, the figural style is unified. The males have large noses and eyes, bold eyebrows, and stocky bodies. The females have short torsos, thin waists, and long, thin arms. In general, economy of means informs the miniatures: the architecture is simple, and the landscapes lack atmosphere. Linear highlights of white and gold enliven the scenes.

Illuminating Antiquity

The miniatures illustrate stories from ancient myths that serve as the bases for Christine's moralizations. The best vividly evoke the story, and sometimes, its moral. For example, the miniature of Cadmus defeating a dragon prominently features a nearby fountain, which, we are told, indicates that knowledge and wisdom always surge forth (fol. 30r).

Elaborate Headgear

The hats and head wrappings of the characters portrayed range widely. Some of the women wear the tall conical hennin of contemporary northern European fashion (for example, Diana and her maidens on fol. 26r). Others wear turbans (such as Io and Cassandra on fols. 30v and 33v). The sorceress Circe is pictured with a snake around her neck and wearing a black hat shaped like a gabled roof (fol. 39r).

The men also wear hats of varying shapes, including turbans. For example, in a scene illustrating the value of courage over possessions, each of four misers is pictured wearing a different type of headgear (fol. 48r).

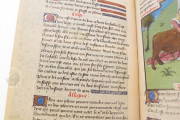

Fashionable Script

The text is written in long lines in French Bâtarde, the formalized cursive preferred for French-language texts. Each of the three sections of the 100 chapters opens with a painted initial, and the headings (texte, glose, and allegorie) are in red. The manuscript has suffered the loss of two leaves with the miniatures and sections of the text for chapters 53 and 56.

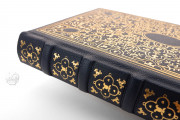

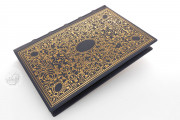

Probably Made for a Duke

There is no firm evidence regarding when, where, or for whom the book was made. Nevertheless, it is entirely possible that it was created for Jacques d'Armagnac (1433-1477), Duke of Nemours. It is also not certain how the manuscript came into the possession of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek: possibly from the collection of the princes of Orange-Nassau of Dillenburg Castle or eventually from the collection of Samuel van Huls (1655-1734). Its current binding of brown leather over boards dates from 1973.

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Hague Epistle of Othéa":

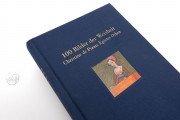

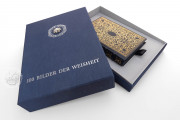

- 100 Bilder der Weisheit - Christine de Pizans Othea-Brief facsimile edition published by Mueller & Schindler, 2009

- Epistre Othea de Christine de Pizan - 100 Imágenes de Sabiduría facsimile edition published by Eikon Editores, 2009