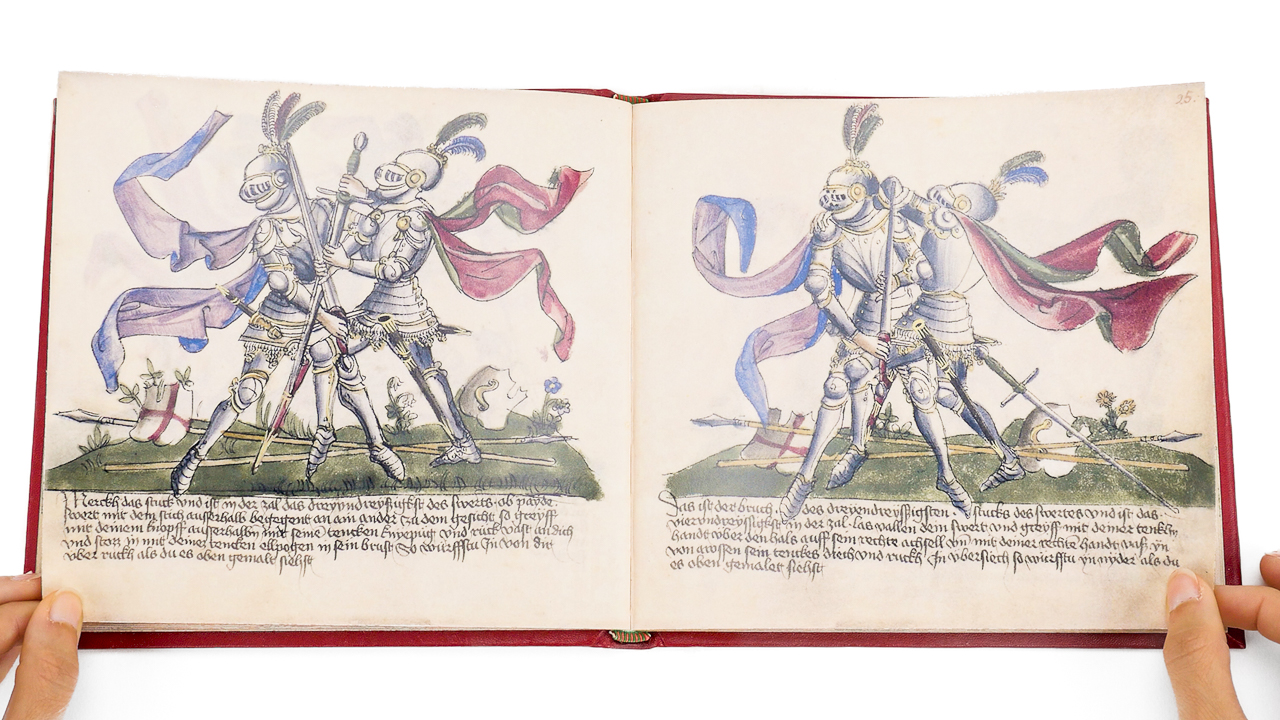

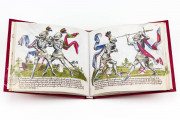

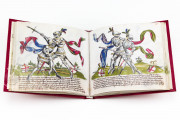

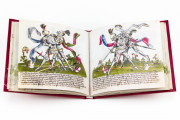

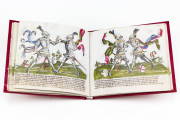

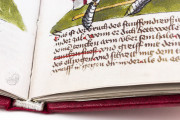

The Kraków Gladiatoria is a handsomely illuminated fight book. Created in Germany in the 1440s, it is a picture manual detailing moves to be employed in a judicially sanctioned duel (trial by combat). Each of the 116 pages features a large painting illustrating a technique of attack accompanied by a brief description in New High German. The unframed paintings are both practical and aesthetically pleasing: each pair of combatants is pictured in a grassy landscape, and the artist has paid careful attention to the details of shields, weapons, armor, and unhelmeted faces.

The Kraków manuscript bears the title Gladiatoria (literally "sword-fighting things"; fol. 1r) and gives the name to the Gladiatoria Group of fifteenth-century German manuscripts that methodically detail devices (or moves) for fighting on the ground (rather than on horseback).

A Mixed Painting Technique

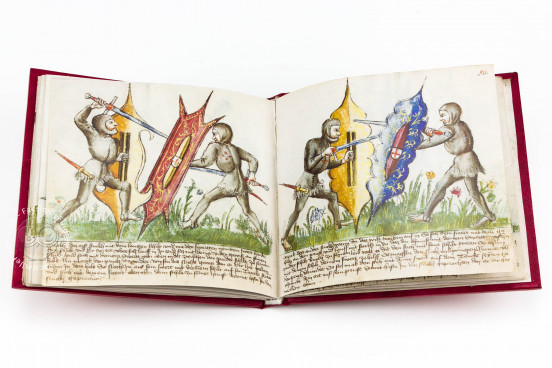

The illustrations are lively by virtue of their subjects, which find the combatants' limbs in various positions, both standing and wrestling. The images are also sensitively drawn and animated by the application of both opaque and translucent colors, including brilliant blues, reds, and greens for plumes on helmets, streaming textiles, and heraldic devices. The heraldry is especially attractive on the long shields (fols. 49v-54r).

Spears, Swords, and Daggers

Although the practice was waning when the manuscript was made, judicial dual could determine guilt or innocence in cases of theft, insult, or injury in the absence of a confession or witnesses. In practice, the combatants should not be wearing armor, but the paintings in the Kraków Gladiatoria show most of the fighters in plate armor.

The weapons treated systematically in the Gladiatoria tradition are spears (fols. 1v-5v), swords and small shields (fols. 7v-33r), and daggers (fols. 33v-49r and 56r-59r), and the paintings illustrating moves described in this textual tradition show the battling men in armor. Also included—and unique to the Kraków manuscript—are images and descriptions of fighting with swords or clubs and long shields, swords and bucklers, single-edged swords (messers) and "Hungarian" shields, and staffs (fols. 49v-55v). Here the combatants fight without the benefit of armor, and—in most cases—without shoes.

Essential Images

The descriptions of the strategies and moves, written by two scribes in Gothic Cursiva, are brief but also detailed. Nevertheless, the images convey the manual's instructions most effectively, and the texts often refer to them. For example, when explaining how to knock an opponent onto his back by taking your sword behind his knee, the text reads "as you see it in the picture above" (fol. 8v).

In Kraków since World War II

The manuscript's early history is untraced. It was undoubtedly in the Preussische Staatsbibliothek by the early nineteenth century. It was one of many manuscripts moved to Grüssau abbey in Lower Silesia for safekeeping during World War II and has been on deposit at the Biblioteka Jagiellońska since the war.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Kraków Gladiatoria": Gladiatoria facsimile edition, published by Orbis Pictus, 2014

Request Info / Price