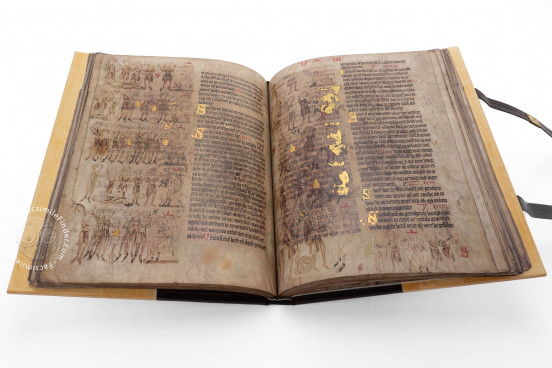

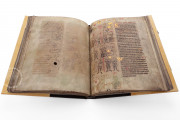

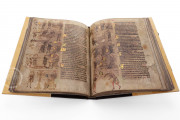

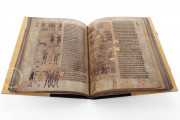

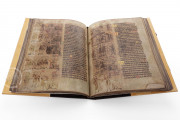

The Dresden Mirror of Saxony is the most richly illuminated extant copy of the first long prose text surviving in the German language. Its text, a compendium in Middle Low German of laws valid in the region of Lüneburg and the Harz, is the single most influential German law code. The manuscript, created in the mid-fourteenth century, perhaps in Meissen, features a continuous series of illustrations of its legal text presented in 924 scenes arranged in the left-hand column of each manuscript page. It is remarkable for the extent of its illumination and the generous use of gold.

The manuscript is one of four fourteenth-century illuminated copies of the text, the others being the Heidelberg Mirror of Saxony, the Oldenburg Mirror of Saxony, and the Wolfenbüttel Mirror of Saxony, the last a copy of the Dresden manuscript.

Laws Made Real

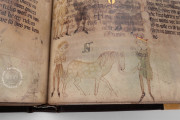

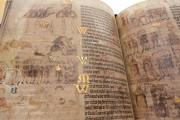

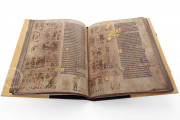

The illustrations are generally presented in the left column of the page on which the text of those laws appears in the right column. They make the abstract legal concepts presented in the text concrete. There are usually four to six scenes per page, but there are instances of as few as two (fols. 56r and 92r) or as many as eight (fol. 45r). There are also instances of paintings filling out the right-hand column.

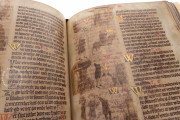

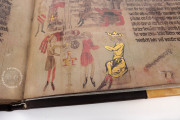

The illustrations present interactions among litigants that bring the abstract laws into the world of contemporary practice. The protagonists are generally distinguished by clothing and attributes, and their gestures tell the stories of the legal transactions. Kings are crowned, bishops wear miters, Jews wear the cone-shaped hats they wore in contemporary Germany, widows are veiled, and laborers wear short tunics.

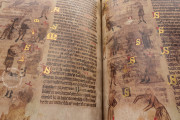

Extraordinary Use of Gold

The Dresden manuscript is remarkable for its generous use of gold leaf for crowns, weapons, reliquaries, dishes, and architectural elements. This sets it apart from the other three illuminated copies of the text and speaks to the probable high social status of its patron.

Careful Coordination

Another remarkable feature of the manuscript—one shared by the Heidelberg and Wolfenbüttel manuscripts—is the use of bulbous Lombard initials in the images and the text to link them. For example, on folio 57r, at the beginning of the section on feudal law, large initials S, P, V, W, and A in each of the vignettes in the left-hand column associates it with the corresponding text (initiated by large initials S, P, V, W, and A in the text) in the right-hand column.

Common Law and Feudal Law

The text was translated into Middle Low German from a lost Latin original by Eike von Ropgow in the first half of the thirteenth century. It is principally concerned with common law (based on custom and agreed-upon general principles) and feudal law (defining reciprocal rights and obligations between lords and vassals). It was widely influential in the northern and eastern German-speaking areas of Europe, as well as the Netherlands.

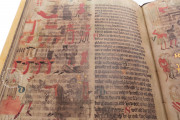

Damage and Restoration

The manuscript was in the possession of August (1526-1586), Elector of Saxony, by 1574, and in 1586 it found itself in the castle of the Elector in Dresden. From there it was transferred to the Landesbibliothek, renamed in 1806 the Königliche Öffentliche Bibliothek, and since 1918 the Sächsische Landesbibliothek. The manuscript, which suffered water damage in World War II, was painstakingly and comprehensively conserved in the 1990s.

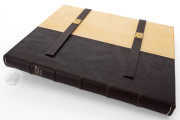

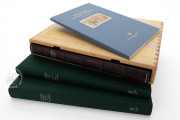

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Dresden Mirror of Saxony": Der Dresdner Sachsenspiegel facsimile edition, published by Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt (ADEVA), 2002

Request Info / Price