Welcome to part 3 of the Faksimile Verlag Story where we deal with the definition of the word facsimile and the differente types of “facsimilization”, from complete to partial.

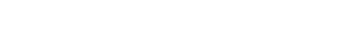

Defined in terms of printing, a facsimile, as a kind of book whose contents reproduce handwritten originals, only became feasible with the invention of printing.

Of course, it would remain too vague if we simply defined the idea of facsimile production as the first time a text, hitherto passed down only in handwritten form, would be reproduced with all its formal elements and using all available technical means. A formulation from CODICES MANUSCRIPTI, the Vienna-based Journal for Manuscript Studies, is helpful here:

A facsimile is the technical-mechanical reproduction of a unique, effectively two-dimensional original, which eliminates as much as possible any manual copying, retains a maximum of the original’s intrinsic and extrinsic criteria, uses all available technical means that guarantee the original’s preservation and accessibility and thus satisfies scholarly and artistic interests. A facsimile must be as true to the original as possible for scholarship and bibliophilia.

Already evident from this definition is that the printing technique used in documenting a unique medieval manuscript does not make a facsimile. Nor does the size of the edition’s print run matter; a facsimile is not an edition because of the number of copies – it is irrelevant whether 250 numbered or several thousand unnumbered exemplars were printed. Crucial are the format, quality and uniformity from the first exemplar to the last.

Facsimile, Reprint, Copy

We can only speak of a facsimile when it is modeled on a unique original, that is, a unicum. The reproduction of a previously duplicated original (identical copying is only feasible with printing) is always called a reprint, even when a reproduction strives to be identical in form and image.

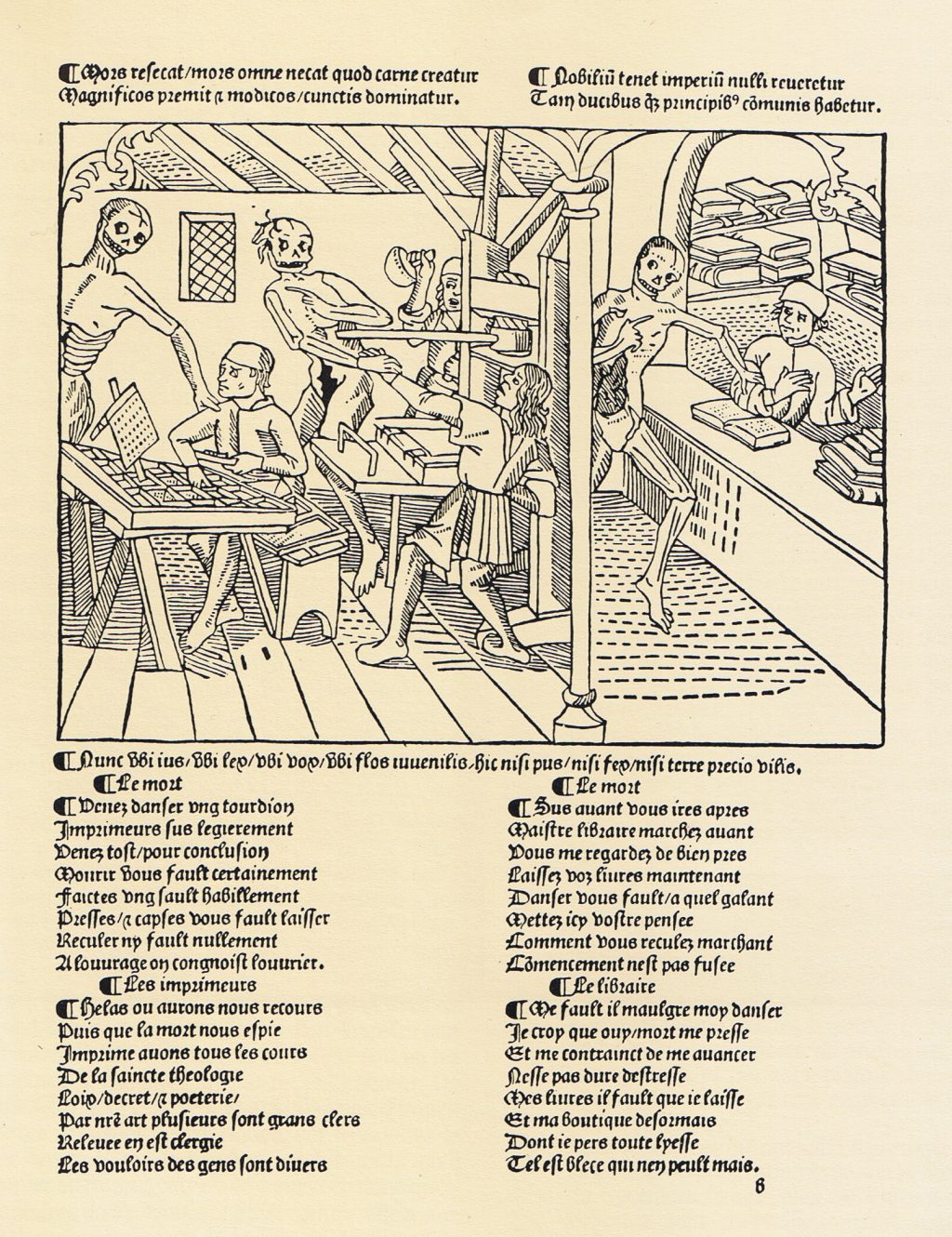

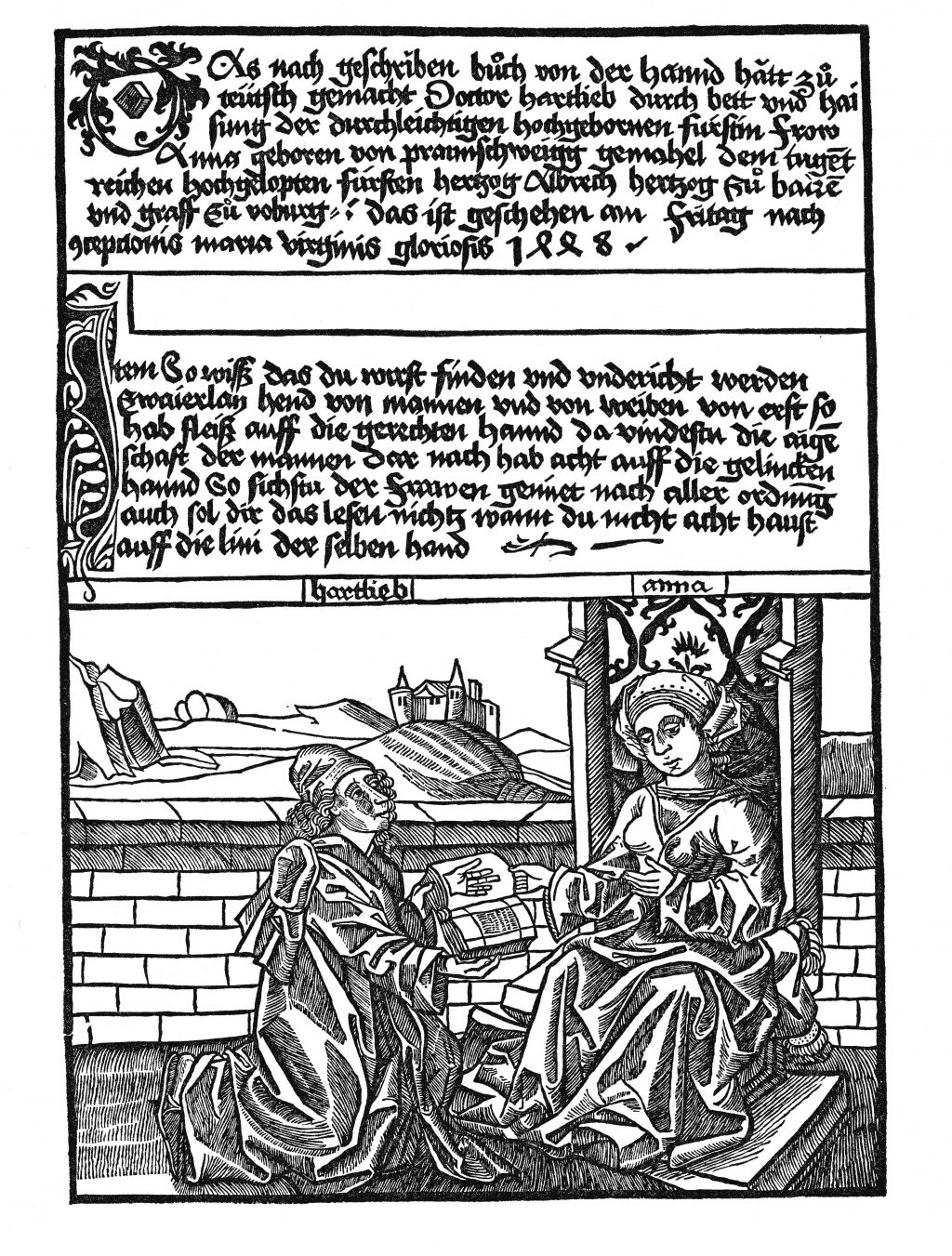

Of course, the boundaries are fluid, such as in the case of incunabula, which are enhanced artistically with individual ornamentation and imaginative, artful pictorial decoration. We need only recall the various exemplars of the Gutenberg Bible (B42), all of which are regarded as unica.

Nevertheless, even hand-colored prints that become unica through individual coloration can become facsimiles through faithful reproduction. This also holds true for glossed prints, given a unique character by their marginalia.

It is clear from the earlier definition of the facsimile that the printing process used is not a criterion for defining the concept. It does not matter with which technology a unicum is reproduced. When such a published work achieves its defined objective relevant to the times, then it is to be called a facsimile. What is decisive is the elimination to the greatest extent possible of manual copying work, for a facsimile has to be objective, not subjective. The facsimile is not simply an individual copy, but instead a likeness printed for the first time and faithfully reproduced. For the collector, the facsimile equates to a manuscript’s first edition.

The modern facsimile not only mirrors the original’s format exactly, but also completely. Only in exceptional, well-founded cases that are documented in the commentary volume may parts only of a manuscript be reproduced true to the original and may blank pages or evidently unimportant texts dating from later times be omitted.

In the past, “partial” facsimile editions were brought out repeatedly. Today’s collectors, as a rule, expect complete reproductions, a concern also shared by the libraries.

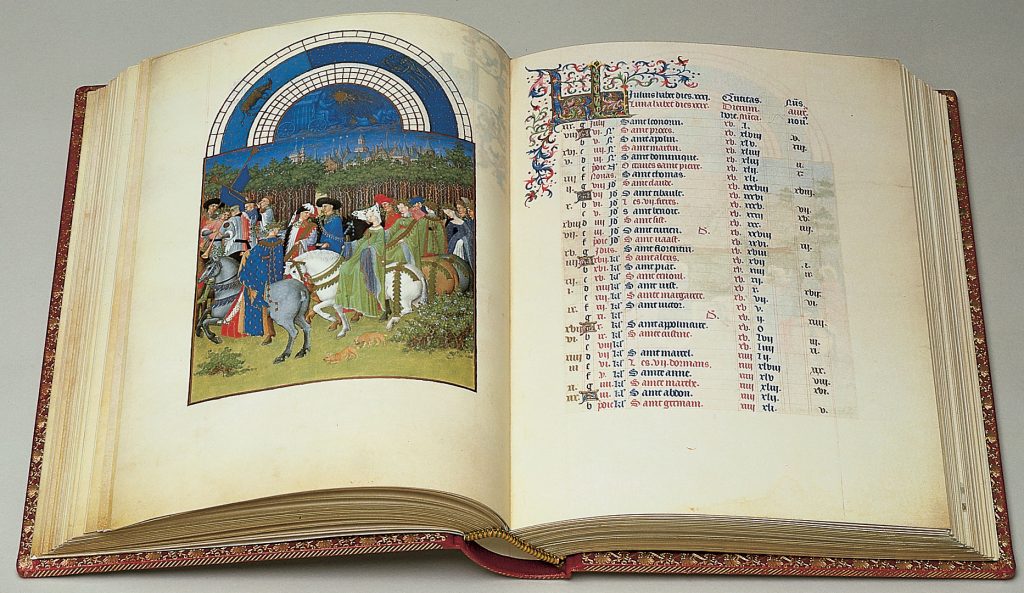

So it happened in the 1970s that a splendid edition of the famous Psalter of Saint Louis were reproduced by France’s National Library (some copies were even reproduced with genuine gold leaf), which contained the complete introductory sequence of pictures and calendarium, all faithfully facsimilized. However, only the miniature pages were reproduced from the actual Psalter and the text-only pages were left out completely. Soon after, a similar thing happened with the Très Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry; it was not until 1984 that the complete facsimile of this queen of medieval manuscripts was facsimilized in toto.

The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, the Très Riches Heures of the Netherlands, from the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, also first appeared as a color reproduction of all miniatures, before the Faksimile Verlag in 2009 was once again able to present the facsimile edition of this, the most unusual book of hours from the entire Middle Ages.

In order to attain the above-mentioned objective of facsimilization – replacing the original as fully as possible in scholarship and bibliophilia – the additional rule applies that in all cases a true facsimile edition must come with a commentary, because even a faithful reproduction still does not make the original of a medieval illuminated manuscript accessible to the modern reader. A facsimile edition’s user, regardless if layman or scholar should be put in the position (figuratively speaking) of looking over the shoulder of the knowledge-steeped librarian.

Only by clarifying the historical context in a good, detailed volume of commentary is it possible to experience manuscripts as they were at the time of their creation. This does not apply necessarily in other cultural spheres in which readers remain aware of spoken, written and pictorial traditions. Judaic manuscripts from the 13th century are for the educated Jew today just as comprehensible as they were 800 years ago.

Coming Next..

- The Story of Faksimile Verlag, Publisher of Fine Facsimile Editions – part 1

- Facsimiles and the Role of Illuminated Manuscripts: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 2

- What is a Facsimile: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 3

- How it All Began: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 4

- From Analog to Digital: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 5

- The Making Process of a Facsimile: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 6

- Challenges and Magic of Facsimile Production: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 7

- Binding, Paper, and Commentary: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 8

- Treasures of the Past: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 9

- Gems of the Middle Ages: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 10

- Flemish, Burgundian, and Biblical Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 11

- Middle Ages through the Manuscripts: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 12

- The Challenges of Gothic Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 13

- Ottonian and Charlemagne’s Art: the Story of Faksimile Verlag – part 14

[/newsletter]