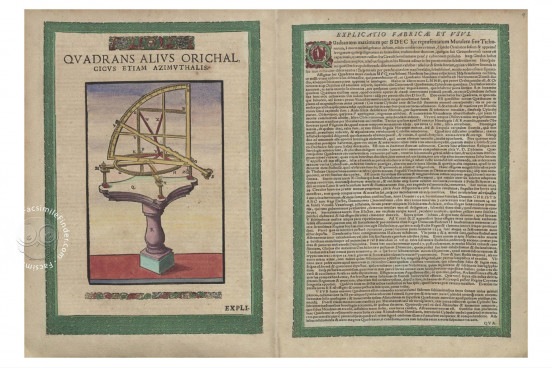

Tycho Brahe's Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica stands as one of the most remarkable scientific books of the Renaissance period. Originally conceived as a showcase of astronomical instruments and later transformed into an elaborate resume for potential patrons, this lavishly illustrated work documents the revolutionary observational tools that would reshape our understanding of the cosmos. The Mechanica contains twenty-two detailed illustrations of astronomical instruments accompanied by comprehensive descriptions, architectural drawings of Brahe's famous Hven observatory complex, correspondence, poetry, and technical specifications.

Produced in fewer than one hundred hand-colored copies on fine paper, this book served not only as a technical manual but as a diplomatic gift designed to secure patronage from European nobility. Its significance extends far beyond its original purpose: the precise measurements obtained with these instruments would later enable Johannes Kepler to discover the laws of planetary motion.

The Architecture and Content of the Mechanica

The work opens with a strategic dedication to Emperor Rudolf II, followed by a laudatory poem by Holger Rosenkrantz, setting a tone of scholarly prestige. The heart of the book consists of twenty-one primary illustrations—originally planned as eighteen woodcuts but expanded to include four additional engravings that Brahe deemed essential. Each instrument is meticulously depicted and accompanied by detailed explanations of its construction, operation, and specific astronomical applications. The twenty-second instrument, Brahe's great brass globe, receives special treatment with an extended description that transitions into a broader discussion of his astronomical accomplishments.

The book's appendix provides architectural plans and descriptions of the Hven observatory facilities, including the famous Uraniborg and Stjerneborg observatories, complete with woodcut illustrations. Technical supplements detail the measuring scales and sighting mechanisms crucial to achieving unprecedented observational accuracy.

The printing itself was a masterpiece of craftsmanship, executed at Wandesbeck using Brahe's personal printing press under the supervision of Hamburg printer Philip von Ohrs. Each copy was individually hand-colored, transforming scientific documentation into works of art suitable for royal libraries.

The Nobleman Who Chose the Stars

Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) defied the expectations of his noble Danish heritage to become Europe's most accomplished pre-telescopic astronomer. Born into one of Denmark's most prominent families and raised by his uncle, Tycho managed to sidestep the traditional path of becoming a courtier or military knight in service to the crown. Instead, he pursued his passion for the humanities and sciences, particularly astronomy, developing exceptional skills in instrument design and celestial observation during his formative travels across Europe. His dedication to astronomy caught the attention of King Frederick II, who recognized Tycho's potential and provided him with unprecedented financial support. In 1576, the king granted him the island of Hven in the Danish straits, where Tycho would build what became Europe's premier astronomical research facility.

Building the Ultimate Observatory

Tycho's vision for astronomical research centered on a fundamental belief: accurate observations required massive, stable, and precisely calibrated instruments. In an era before telescopes, when all observations relied on naked-eye measurements, most astronomers struggled with inadequate equipment that produced unreliable data. Tycho revolutionized observational astronomy by designing and constructing enormous instruments that minimized error and maximized precision.

Beginning his observations on his thirtieth birthday, December 14, 1576, even before the observatory's completion, Tycho maintained a rigorous observing program with the help of numerous assistants. His team focused primarily on determining accurate stellar positions and tracking the movements of the sun, moon, and planets to develop the most precise understanding of their orbits available at the time. This systematic approach to data collection set new standards for astronomical research that would influence scientific methodology for generations.

From Patronage Crisis to Lasting Legacy

The death of King Frederick II in 1588 marked the beginning of Tycho's difficulties with the Danish court. Finding himself out of favor with the new regents and facing the coronation of the less sympathetic King Christian IV in 1596, Tycho recognized that his lavish research expenditures would no longer receive royal support.

This crisis prompted him to leave Hven in 1597 and seek patronage elsewhere, eventually settling at Heinrich Rantzov's estate in Wandesbeck, outside Hamburg. There, Tycho completed the Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica, transforming what had been a project in progress since the 1580s into both a scientific treatise and a sophisticated appeal for patronage directed at Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. The strategy proved successful—Rudolf welcomed Tycho to Prague in 1598, providing him with a castle to continue his work.

Though Tycho died in 1601 before completing his research program, his meticulous observations bore fruit through his assistant Johannes Kepler, who used Tycho's precise measurements to discover that planetary orbits were elliptical rather than circular and to formulate the first two laws of planetary motion, published in his groundbreaking Astronomia Nova (1609).

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica": Tycho de Brahe: Astronomiae Instauratae Mechanica facsimile edition, published by Pytheas Books, 2002

Request Info / Price