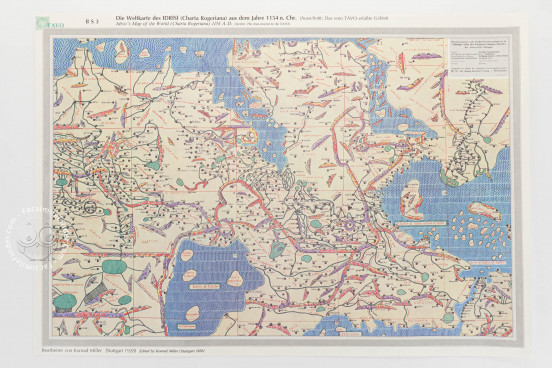

The Tabula Rogeriana stands as a monumental testament to the intellectual symbiosis of the 12th century, representing perhaps the most advanced geographical work of the Middle Ages. Commissioned in 1138 by the Norman King Roger II of Sicily, this masterpiece was not merely a map, but the culmination of a fifteen-year scientific endeavor led by the distinguished Andalusian geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi.

The creation process was rigorously scientific. Al-Idrisi and the King established a dedicated academy, interviewing travelers, merchants, and sailors passing through Sicilian ports.

The Convergence of East and West in Norman Sicily

To understand the genesis of the Tabula Rogeriana, one must first understand the unique environment of its birth. Sicily under King Roger II was a "palimpsest" civilization where Norman administrative efficiency, Greek Byzantine artistry, and Arab scientific prowess coexisted.

Roger II, an ambitious and intellectually curious monarch, sought to consolidate the knowledge of his expanding realm. He was not satisfied with the symbolic, often religiously motivated Mappa Mundi typical of Christian Europe, which prioritized theology over topography. Roger desired empirical precision. To achieve this, he turned to the Islamic world, which was then enjoying its Golden Age of science and scholarship.

In 1138, Roger invited Muhammad al-Idrisi, a scion of a noble family with roots in Ceuta and Córdoba, to his court. Al-Idrisi was a man of the world, a traveler who had traversed North Africa and Western Europe, possessing a geographical literacy that far outstripped his European contemporaries. The King’s proposition was simple yet grand: to create a representation of the known world that was strictly factual, shedding the mythological beasts and biblical guesswork of the past in favor of verifiable data.

The Scientific Method of Al-Idrisi: Data Collection and Verification

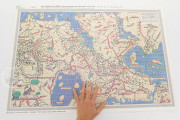

The creation of the Tabula Rogeriana was arguably one of the first major state-sponsored scientific research projects in history. The process, which spanned from roughly 1138 to 1154, utilized a methodology that was startlingly modern. Al-Idrisi did not simply copy existing maps; he interrogated the world.

Roger II and Al-Idrisi established an academy of sorts in Palermo. They summoned travelers, merchants, pilgrims, and sailors who docked at the bustling Sicilian ports. Al-Idrisi interviewed these seasoned wanderers individually and in groups, recording their observations regarding distances, travel times, coastal distinctiveness, and local customs.

However, Al-Idrisi applied a strict filter of skepticism to this raw data. As noted in historical accounts, he retained "only that part... on which there was complete agreement and seemed credible, excluding what was contradictory."

When gaps in knowledge appeared, King Roger II would dispatch his own agents and draftsmen to distant lands to gather fresh intelligence and verify existing claims. This was an active, empirical engagement with geography. The project also drew heavily upon the intellectual lineage of the Abbasid Caliphate and the Balkhi school of geography, blending the mathematical rigors of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography with the rich, descriptive tradition of Arab travel writing.

The Structure of the Atlas: Climatic Zones and Sectional Maps

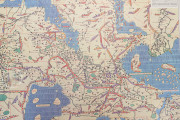

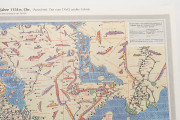

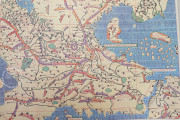

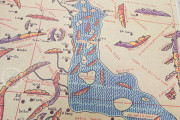

The physical organization of the Tabula Rogeriana was rooted in the Ptolemaic system of "climates." The known world—stretching from the Canary Islands in the west to Korea in the east, and from the sub-Saharan regions of Africa to the icy fringes of Scandinavia—was divided into seven horizontal climatic zones. Al-Idrisi further subdivided each of these seven climates into ten vertical sections.

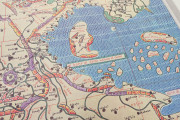

This grid system resulted in 70 double-page sectional maps. When assembled, these sections formed a massive, rectangular view of the Eurasian and African continents. Unlike modern maps with North at the top, the Tabula Rogeriana followed the Islamic cartographic tradition of placing South at the top, a respectful orientation that placed the holy city of Mecca in a central, upper position.

What distinguished these maps was their consistency. Despite the lack of modern satellites, Al-Idrisi utilized a coordinate system that maintained scale across the different sections. The level of detail was unprecedented: the maps depicted river courses, mountain ranges (often stylized in rich colors), major cities, and trade routes. While the coordinates were not accurate by 21st-century GPS standards, they were a quantum leap forward in relative accuracy for the 12th century.

The Lost Silver Disc and the Concept of a Spherical Earth

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of the Tabula Rogeriana’s history is the loss of its centerpiece. The manuscript book was actually the accompanying text to a far more ambitious object: a massive silver planisphere. Roger II commissioned a disc of pure silver, weighing approximately 300 pounds (140 kg) and measuring nearly six feet in diameter.

On this silver canvas, Al-Idrisi engraved the composite map of the world. This was not a flat-earth representation; the very existence of the planisphere, and Al-Idrisi's calculations suggesting a distinct understanding of the Earth’s circumference (which he calculated with an error of less than 10 percent), hinted at a sophisticated grasp of the planet's spherical nature and even the concept of gravity.

Tragically, this silver masterwork did not survive long after its creation. In the chaotic uprisings of 1160, led by Matthew Bonnellus against the Sicilian crown, the palace was looted, and the great silver disc was broken up and melted down, presumably for its monetary value. The world lost a unique artifact, leaving only the parchment manuscripts to carry Al-Idrisi’s legacy forward.

Geographical Scope and Descriptive Accuracy

The text accompanying the maps—the Nuzhat al-mushtāq proper—provides a fascinating window into the 12th-century world. Al-Idrisi offered detailed commentary on the physical, cultural, political, and socioeconomic conditions of the regions he mapped.

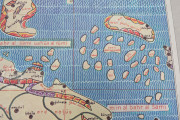

The accuracy of the atlas varies depending on the region's proximity to Sicily. The depictions of the Mediterranean basin, Europe, and North Africa are remarkably precise. Al-Idrisi’s description of the Nile, for instance, was so authoritative that it remained the standard reference for centuries; his placement of the lakes that feed the Nile mirrors the findings of 19th-century explorers like Baker and Stanley, a testament to the quality of the Arab sources he utilized.

Conversely, regions further afield, such as Southeast Asia and China, were depicted with less detail and more abstraction, reflecting the limitations of the travel networks of the time.

Crucially, the text is secular in nature. Unlike Christian maps of the era, which might center on Jerusalem or depict the Garden of Eden, Al-Idrisi’s work focused on "countries and districts, coasts and lands, gulfs and seas, watercourses and river mouths." It was a tool for governance and trade, not a theological statement.

The Legacy and Survival of the Book of Roger

Despite the destruction of the silver disc, the manuscript version of the Tabula Rogeriana enjoyed immense popularity and longevity. For three centuries, it remained the most accurate map of the world available. It bridged the gap between the decline of classical knowledge and the European Age of Discovery.

The work was widely copied and distributed. Today, ten manuscript copies survive in various states of preservation, with five containing the complete text. The oldest extant copy, dating to roughly 1300-1325, is held at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (MS Arabe 2221). Another significant copy, produced in Cairo in 1553, resides in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. The most complete manuscript, containing the world map and all seventy sectional maps, is preserved in Istanbul.

The Tabula Rogeriana also influenced later generations of cartographers. The "Little Idrisi," an abbreviated version created for Roger II’s son, William II, ensured the continuity of this geographical knowledge. By the time the work was translated into Latin by Gabriel Sionita in Paris in 1619, the world had changed, yet the Book of Roger remained a respected source of historical data.

Extant Manuscript Copies of the Tabula Rogeriana (1154)

- Bibliothèque nationale de France (Paris), MS Arabe 2221 (also catalogued as Suppl. Arabe 892)

- Bibliothèque nationale de France (Paris), MS Arabe 2222 (also catalogued as Suppl. Arabe 893)

- Süleymaniye Library (Istanbul), Ayasofya (Hagia Sophia) MS 3502

- Köprülü Library (Istanbul), MS 955

- Cyril and Methodius National Library (Sofia), MS Or. 3198

- National Library of Russia (Saint Petersburg), MS Ar. N.S. 176

- British Library, MS Loth 722 (also cited as MS Ar. 617)

- Dār al-Kutub (Cairo), Jugrāfīyā 150 (Gezira 150)

- Bodleian Library (Oxford), MS Pococke 375

- Bodleian Library (Oxford), MS Greaves 42

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Tabula Rogeriana":

- Weltkarte des IDRISI (Charta Rogeriana) aus dem Jahre 1154 n. Chr. (Ausschnitt, das vom TAVO Erfaßte Gebiet) facsimile edition published by Reichert Verlag, 1981

- Weltkarte des Idrisi vom Jahr 1154, Charta Rogeriana facsimile edition published by Brockhaus / Antiquarium, 1981