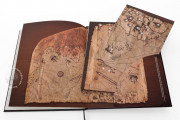

The Piri Reis World Map, created in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis, stands as one of the most significant cartographic documents of the Age of Discovery. Drawn on gazelle skin, this portolan chart synthesizes Eastern and Western geographical knowledge, preserving details from now-lost maps. It is renowned for its depiction of the Atlantic Ocean and the Americas, offering a unique glimpse into how they were perceived shortly after their initial European contact.

The map that survives today is only a fragment of a much larger work. The original document was likely a complete world map that also covered the Indian Ocean and Asia.

A Synthesis of Twenty Sources

Piri Reis did not travel to the Americas himself; rather, his map is a compilation derived from approximately twenty distinct source maps named by Piri Reis himself. In his inscriptions, he credits a diverse array of references, including eight Ptolemaic maps, four contemporary Portuguese maps depicting India and China, an Arabic map of India, and, most notably, a map drawn by Christopher Columbus. This meticulous synthesis allowed him to depict the coasts of Europe, Africa, and the newly discovered Americas with remarkable detail for the era.

The Admiral Behind the Map

Piri Reis (born Muhiddin Piri) was a prominent Ottoman admiral and geographer. He began his naval career alongside his uncle, the famous privateer Kemal Reis, taking part in campaigns throughout the Mediterranean. In addition to the 1513 World Map, Piri Reis is well known for the Kitab-ı Bahriye (Book on Navigation). Completed in 1521 and revised in 1526, this book served as a detailed guide for sailing the Mediterranean Sea. His role in the navy gave him access to foreign charts captured during battles, which allowed him to gather the diverse sources necessary for his work.

The Columbus Connection

Perhaps the most historically significant aspect of the Piri Reis map is its direct link to Christopher Columbus. Piri Reis explicitly states that the western region of his map was based on a chart drawn by "Colombo." This claim is vital because Columbus's original map of the Americas has been lost to history. Consequently, the 1513 map serves as the only extant document that preserves the geographical ideas and coastal outlines recorded by Columbus during his voyages, particularly his exploration of the Caribbean and the coast of South America.

Depicting the Unknown

The map is famous for its representation of the South American coastline, which extends southward with surprising accuracy. While some fringe theories suggest it depicts an ice-free Antarctica, the map actually shows a landmass curving eastward, likely a result of Piri Reis trying to reconcile the South American coast with the Ptolemaic concept of a massive southern continent, Terra Australis Incognita. The map also includes mythical islands like Antillia, blending empirical observation with medieval legend.

UNESCO Recognition

Recognizing its immense historical value, UNESCO included the Piri Reis World Map in the Memory of the World Register in 2016. This designation highlights the map not only as a masterpiece of Ottoman naval cartography but also as a crucial document for world history. It physically resides in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul, where it was rediscovered in 1929, serving as a testament to the cross-cultural exchange of knowledge during the early modern period.

Insights from the Commentary

A Portolan at the Threshold of Worlds

The Piri Reis World Map occupies a liminal position between medieval cosmography and Renaissance nautical science. Executed in 1513 on gazelle skin parchment, it adopts the practical language of the portolan chart—with rhumb lines, compass roses, and coastal emphasis—while simultaneously gesturing toward a global vision of the inhabited world. Its circular conception, organized around a hypothetical center near northeast Africa, reflects contemporary attempts to reconcile inherited worldviews with unprecedented geographic discovery.

The Columbian Inheritance

The western portion of the surviving fragment preserves what is widely regarded as the earliest extant cartographic record of Columbus’s Atlantic discoveries. Place-names rendered in Italian forms, distortions consistent with Columbus’s belief that Cuba was part of the Asian mainland, and the anomalous configuration of the Caribbean collectively confirm reliance on a lost Columbian prototype. In this sense, the map is not merely influenced by Columbus—it is a material witness to his vanished cartography, surpassing later European representations in evidentiary value.

An Ottoman Perspective on Global Discovery

Beyond its geographic content, the Piri Reis map functioned as a vehicle of knowledge transfer into the Ottoman world. Turkish toponyms along the African coast, annotations explaining Iberian discoveries, and references to the Treaty of Tordesillas underscore the map’s role in translating European expansion into an Islamic intellectual framework. In doing so, it exemplifies the Ottoman engagement with global exploration not as passive reception but as critical assimilation and reinterpretation.

Survival, Fragmentation, and Modern Rediscovery

Only about one third of the original world map survives, its eastern sections lost to damage and truncation. Rediscovered in 1929 in the Topkapı Palace Museum Library, the fragment immediately attracted international scholarly attention. Its later inscription in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register affirms its status as a unique documentary bridge between cultures, epochs, and epistemologies, uniting art, navigation, and historical testimony in a single artifact.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Piri Reis World Map": Pîrî Rêisîn Dúnya Haritası. World Map of Piri Reis 1513 facsimile edition, published by Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, 2014

Request Info / Price