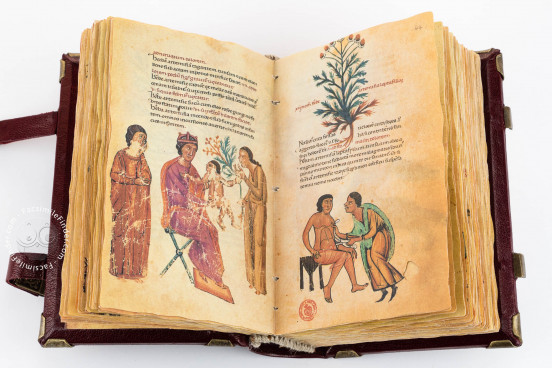

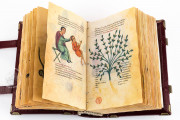

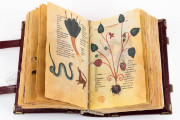

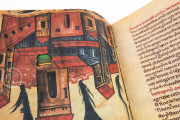

Thought to have been produced in the court circle of Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Jerusalem and Sicily, the Medical Miscellany in the Laurenziana, made in southern Italy in the thirteenth century, focuses on the curative properties of plants—and to a lesser extent, animals. Its texts and illustrations are copied from one or more late antique manuscripts. The high-quality illumination includes full-page author portraits, a group portrait of ancient physicians, and cityscapes. Hundreds of depictions of medicinal plants and animals illustrate the texts.

The principal texts are an herbal attributed to the second-century CE philosopher Apuleius (fols. 27-147), a text on remedies derived from animal substances by the fourth-century Roman physician Sextus Placitus (fols. 150-176), and On Female Herbs, a text that relies on the herbal of the first-century CE Greek physician Dioscorides Pedanius (fols. 179r-228r).

Eleven or More Painters

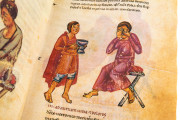

The hundreds of illustrations were produced by at least eleven artists, whose work can often be differentiated by the treatment of human faces and hair. For example, two painters give their figures rosy cheeks, but only one of them renders male figures with short, blunt-cut brown hair (as in the scenes of betony used to cure maladies of the head and eyes on fols. 21v-22r).

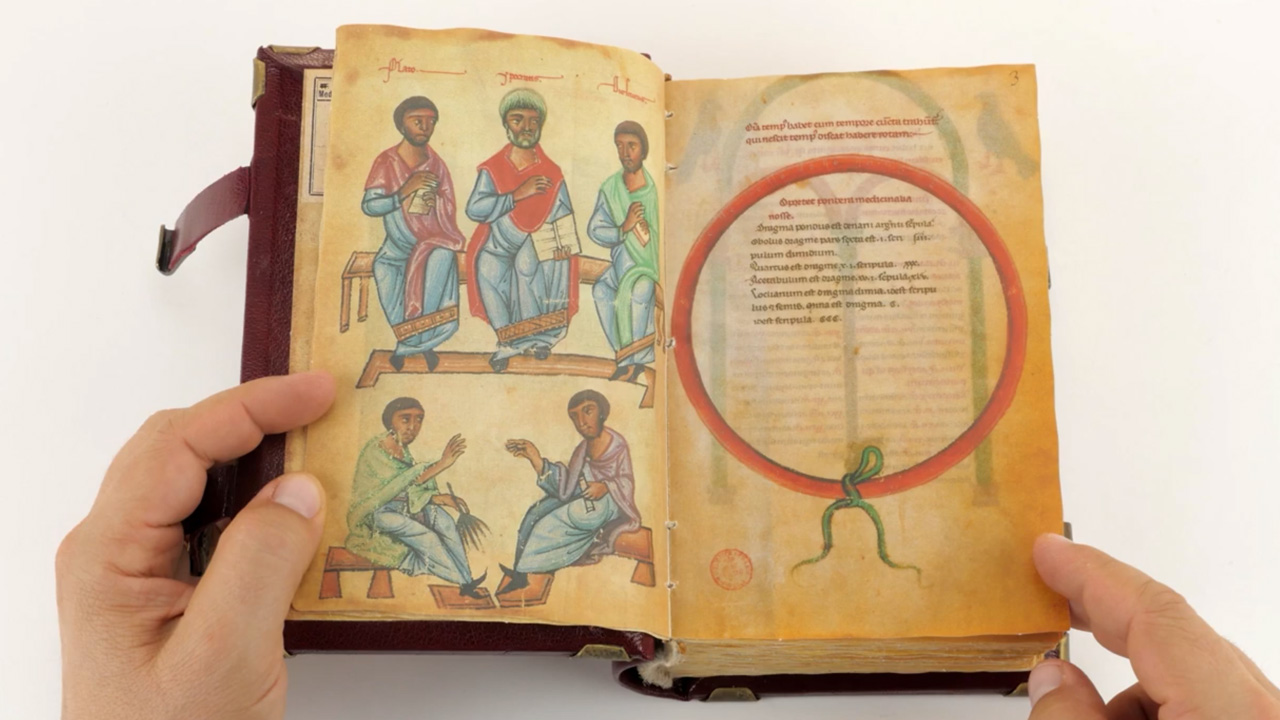

A supremely talented artist was responsible for just one image, the group portrait of ancient physicians (fol. 2v). Apuleius (labeled Plato), an elderly Hippocrates, and Dioscorides form an elegant grouping on a shared bench. They are sumptuously garbed, with gold trim at the hems of their tunics. Below them, a pair of physicians converse.

Emphasis on Medicinal Use

The herbal of Pseudo-Apuleius is arranged by malady, and the pictorial emphasis is on the plants in action. There are illustrations of botanical specimens, but fully 150 scenes include humans, and most show the practice of medicine.

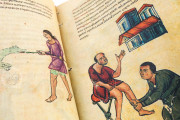

The illustration for rabies encapsulates a series of actions: the bitten man is treated with verbena and wheat, the dog that bit him having been killed by a sword, and a hen awaits the chance to test the grains of wheat used in the cure (fol. 34v).

Emotions Expressed

Many of the scenes of medical procedures are dramatic, with hand gestures or facial expressions betraying anxiety or pain. For example, in the scene of a practitioner administering squill to a man suffering from edema, the distress of a woman—perhaps the patient's mother or wife—is written on her face (fol. 74v). Another patient betrays his stomachache in his furrowed brow and frown (fol. 24r).

Elegant Script

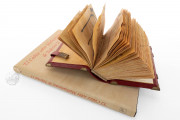

A single scribe wrote the text in long lines (a single column) in a careful Gothic Rotunda, the rounded form of Gothic script favored in Italy. Headings in red, working in conjunction with the numerous illustrations, make it easy to locate specific remedies.

The text and images of the Laurenziana codex are closely related to those of the Medicina Antiqua, a medical miscellany in Vienna also made in southern Italy in the thirteenth century. Perhaps both manuscripts were copied from the same sixth-century exemplar.

Ex Libris Giovanni de' Medici

The manuscript was in the collection of Giovanni de' Medici (1475-1521; later Pope Leo X) by 1508, when, as a cardinal, he took his books to Rome. It was among the volumes in the private collection of the Medici family that constituted the core collection of the Biblioteca Laurenziana when it opened to the public in 1571. In 1808, the Dominican convent of San Marco's collection merged with the Laurenziana to form the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana.

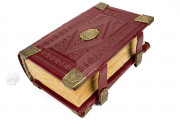

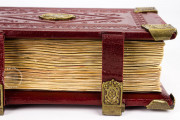

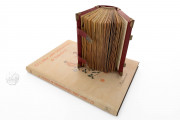

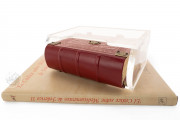

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Medical Miscellany": Códice Sobre Medicamentos de Federico II facsimile edition, published by Patrimonio Ediciones, 2002

Request Info / Price