A masterpiece of Insular manuscript painting and one of the most iconic books of the Middle Ages, the Lindisfarne Gospels melds Insular and Mediterranean traditions in its illumination. The imposing manuscript of the Gospels—the Christian biblical books that describe the life, ministry, and death of Jesus—was produced around 700. Most scholars accept that it was written and illuminated by Eadfrith, a monk of the Benedictine monastery of Lindisfarne. Its four full-page evangelist portraits draw direct inspiration from Mediterranean sources, while its incipit pages, which dissolve the boundary between text and image, are Insular in tradition.

Relying on intense, jewel-like colors and fields of interwoven creatures for its stunning beauty, the book was made by monks for monks. It at once makes physical the holy words of the Gospels and yet seems to transcend the physicality of brush, paint, and parchment through its calm balance and seemingly infinite intricacy.

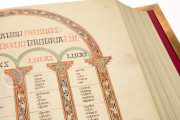

Lindisfarne Gospel Book: Gospel Concordance

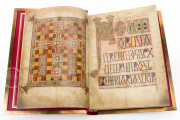

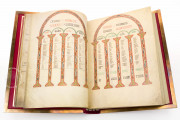

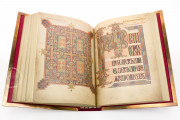

The manuscript opens with a series of prologues followed by sixteen pages of canon tables—columns of numbers keyed to the biblical text that indicate the concordance of passages among the Gospels (fols. 10-17). The canon table pages feature painted arcades composed of various interlace designs that harmonize across each opening of facing pages. Many designs comprise stylized birds and serpents that intertwine and bite on strands of the interlace.

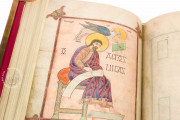

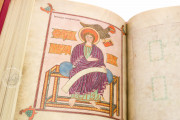

Lindisfarne Gospels Images: Portraits in the Tradition of Late Antiquity

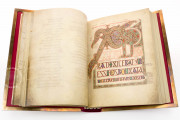

Although the Lindisfarne Gospels was created in northern England, its portraits of the purported authors of the four Gospels—Saints Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—reveal their artist's acquaintance with the author portrait tradition of late antique manuscript art of the Mediterranean basin (fols. 25v, 93v, 137v, and 209v). They are shown either in the act of writing their texts or—in the case of Saint John—holding a scroll and staring out at the viewer.

Interlace of Infinite Fascination

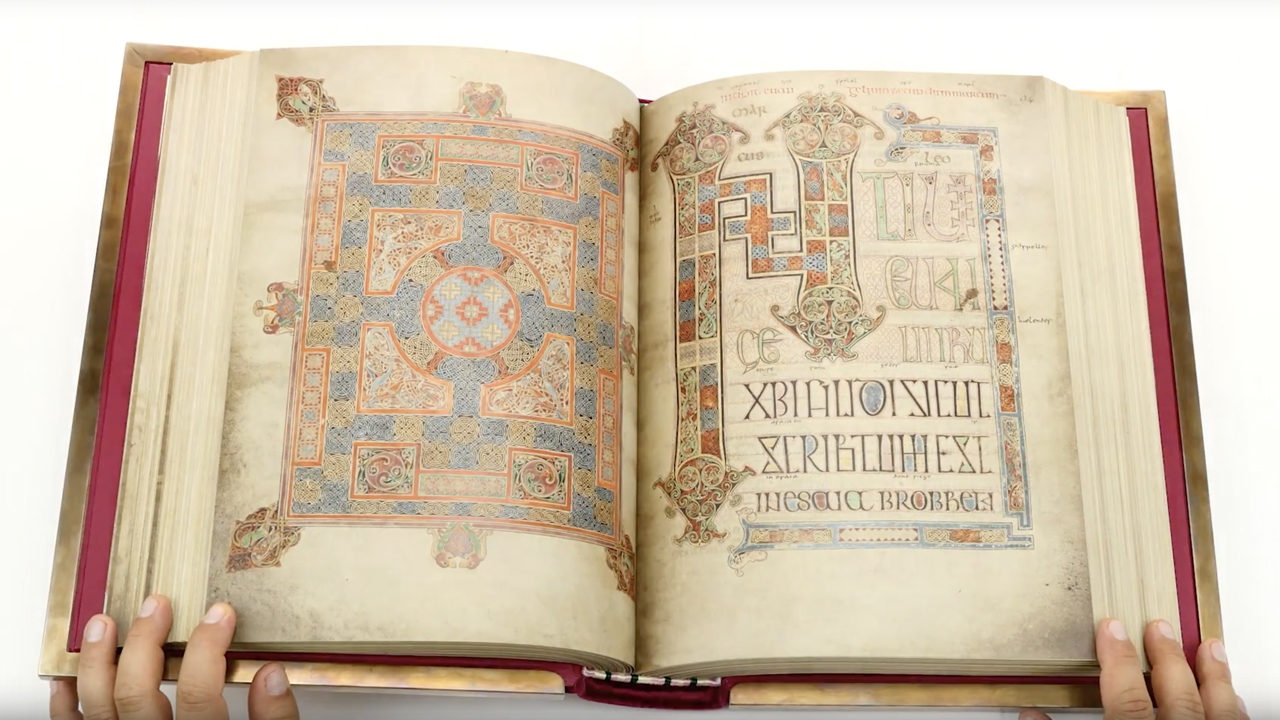

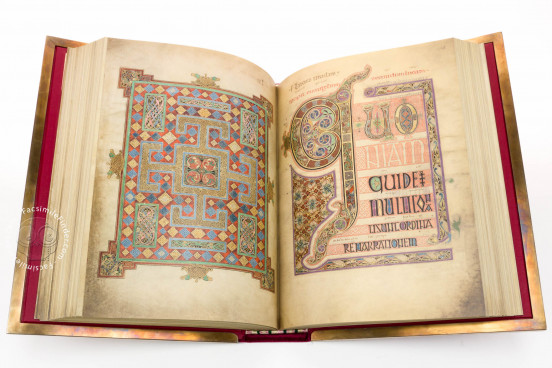

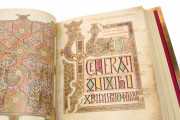

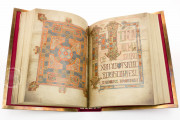

Each Gospel opens with a carpet page—a page given over entirely to intricate carpet-like painted decoration—facing an incipit page—a page on which the opening letters of a text are enlarged and painted. The carpet pages are all arranged so that their patterns of interlace form a cross on the ground, with much of the knotwork appearing as stylized animals (fols. 26v, 94v, 138v, and 210v).

The incipit pages present highly stylized letterforms that diminish in size as the text unfolds, with the first three or four letters as monograms of panels of interlace (fols. 27r, 95r, 139r, and 211r). The interlace framing elements have a small opening in the lower right corner of the page, signaling that the text continues onto the following pages.

The Characteristic Script of the British Isles

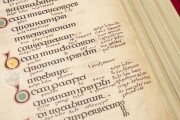

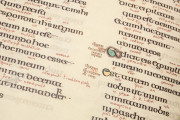

The manuscript's text is a glorious example of the Insular adaptation of the late Roman Half-Uncial script. The text is written in two columns, with each new sense unit beginning on a new line. Each clause begins with an enlarged letter or letters, how large depending on the strength of the sense division from the forgoing. Those initial letters often feature touches of color and are surrounded by red dots.

Writing between the Lines

Around 970, Aldred, provost of the Lindisfarne community in exile at Chester-le-Street near Durham, added an interlinear translation into Old English of the manuscript's text, creating the earliest surviving version of the Gospels in English. He also added a colophon recording the community's tradition concerning the manuscript's creation by Eadfrith.

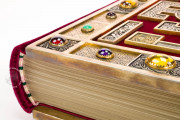

From Durham to the British Library

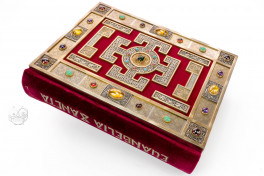

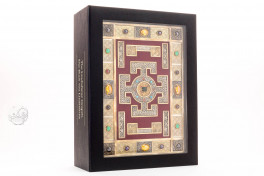

The monastery at Lindisfarne was attacked and looted by Vikings in 793, but the Lindisfarne Gospels was safely transported away. It was in the collection of Durham Cathedral by the twelfth century. It found its way via the collections of Thomas Turner (sixteenth century) and Robert Bowyer (d. 1621) into the library of the antiquary Robert Cotton (1571-1631). Robert's grandson, John Cotton (1621-1702), bequeathed the Cotton collection of books and manuscripts to Britain "for Publick Use and Advantage." It was one of the foundation collections of the library of the British Museum. The chased silver of its 1853 binding imitates the manuscript's interlace decoration. The manuscripts of the British Museum library were transferred to the British Library upon its establishment in 1973.

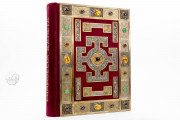

We have 2 facsimiles of the manuscript "Lindisfarne Gospels":

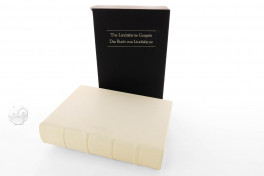

- Buch von Lindisfarne (Leather Edition) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 2002

- Buch von Lindisfarne (Victorian Binding Edition) facsimile edition published by Faksimile Verlag, 2002