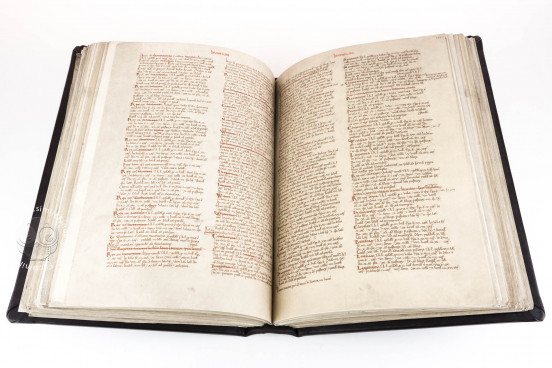

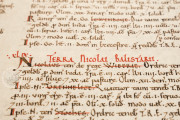

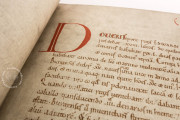

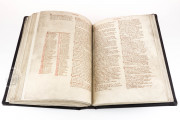

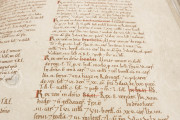

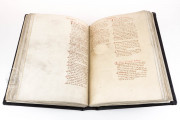

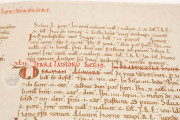

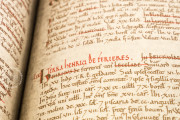

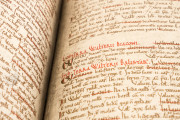

Great Domesday Book—also known as the Book of Winchester, the King's Roll, and the Book of the Treasury—was copied in 1086 and 1087 at Winchester. It records information about thousands of properties in England. Together with Little Domesday Book, it was the foundation of most of England's property records through the Middle Ages. The book is arranged by shire, and each county is introduced by a large red capital letter, with major headings in red Rustic Capitals.

On Christmas Day in 1085, William I "the Conqueror," King of England, commissioned a survey of his kingdom. For the next several months, his commissioners compiled detailed records of every church, manor, and field. Although the intended purpose of this endeavor is debated, it unquestionably resulted in a unique document.

A Survey of Eleventh-Century England

Although the intention was to collect information about the whole realm in one volume, Great Domesday Book is not comprehensive. Some cities, such as London and Winchester, and most of the counties of Cumbria, Northumbria, and Durham in the north are not included. Essex, Suffolk, and Norfolk are only represented in the companion Little Domesday Book.

Organizing a Vast Body of Information

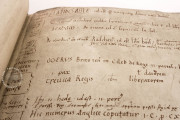

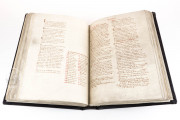

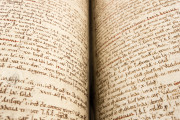

Great Domesday Book was written, for the most part, by a single scribe in the Transitional Script of the long twelfth century. The text was systematically corrected by a second scribe, and additions and corrections were made by four others. Running titles in the upper margin of each page inform the reader of the shire being described on that page, an innovative feature of the book.

Most entries begin with an account of the main town of the shire, followed by a list of the chief landholders. Then follows a record of royal lands; lands of the archbishopric, bishoprics, and abbeys; lay properties (generally called manors); smaller towns; and parish churches. Each entry includes an enumeration of subtenants, plows, woodlands, meadows, pastures, mills, and fishponds on a property, as well as the property's value.

A Day of Judgment

The Dialogue of the Exchequer of the late 1170s reports that the book was called Domesday, the Day of Judgment, because the information written within it could not be appealed or altered, akin to the sentence received by the Christian faithful at the Last Judgment.

A Very Big Book

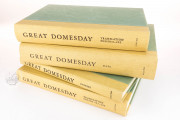

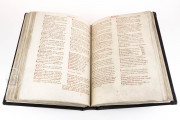

The book has been bound at least six times over the centuries. It was bound as a single volume until 1986, when it underwent conservation work for its 900th anniversary and was bound into two volumes, with fols. 1-188 in the first and fols. 189-382 in the second volume.

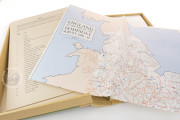

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Great Domesday Book": Great Domesday Book – The Millennium Edition facsimile edition, published by Alecto Historical Editions, 2000

Request Info / Price