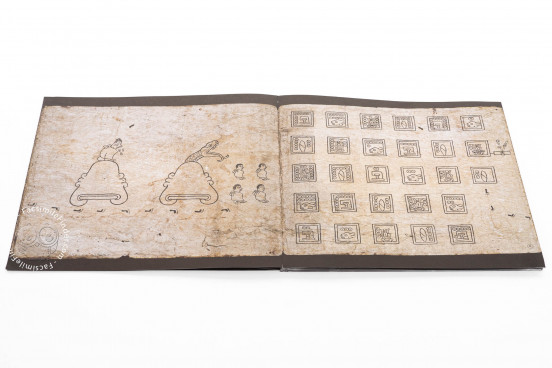

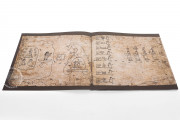

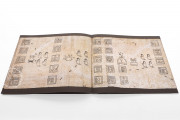

The Codex Boturini is a manuscript screenfold that chronicles the 200-year journey south of the Mexica to Tenochtitlán, stopping at nearly thirty settlements and establishing cultural practices. It was created in the first half of the sixteenth century, presumably in the Valley of Mexico (the highland plateau where the Mexica eventually settled): the earliest surviving manuscript that records the Mexica migration. The history, which is truncated by a loss at the end, is presented in twenty-two pages of pictographs—symbols representing objects, actions, or ideas.

The screenfold comprises sheets of amate paper (amatl in Nahuatl) made from the inner bark of the fig tree. These form a strip nearly five and a half meters (18 feet) long. A thin layer of plaster created a smooth surface for the painting, which is confined to one side of the strip.

The Work of a Single Painter-Scribe

The story reads from left to right, and the single painter-scribe also worked from left to right. The painter-scribe first drew the pictographs in thin black lines, which he then traced with the bold black strokes we see now. The painter-scribe also drew thin red lines connecting some of the year signs, but these remain preliminary. None of the outlined pictographs is colored, suggesting the document was left unfinished.

From Aztec to Mexica

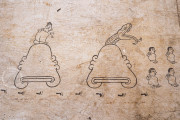

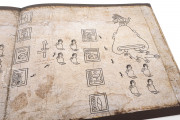

The opening pages report the motivation for the migration, with the departure from Atzlán (depicted as an island) at the summons of the god Huitzilpochtli (p. 1). There follows the critical moment when the former Aztecs become the Mexica, Huitzilpochtli's chosen people, with the introduction of human sacrifice (p. 4).

New Customs Distinguish the Culture

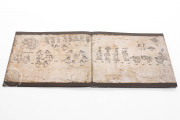

Human sacrifice was not the only new cultural practice introduced during the Mexica migration. Also new was the custom of drinking pulque (octli in Nahuatl), an intoxicating beverage made from fermented agave; its discovery and production are pictured in the manuscript (pp. 13-14). Also new was the ceremony of the New Fire, a ritual held every fifty-two years.

Recurring Signs

The visual vocabulary of the Codex Boturini includes (cane-shaped) speech scrolls. Although what is said is not specified, the speech scrolls help identify the motivations behind the depicted actions. Small footprints link related pictographs; for example, the pictograph for the agave plant is connected by footprints to the creation of its intoxicating drink on the following page. Conspicuous tears mark the cheeks of many figures during times of distress.

Years and Years

Year signs take the customary form of the animal or object of its name and a series of balls for its number. These are always contained within neat square frames. They appear in groups, indicating the number of years the Mexica settled in a particular place, ranging from one to twenty-eight.

Named for Its Eighteenth-Century Owner

Faint inscriptions in Nahuatl were added, probably in the sixteenth century, but certainly not a part of the original plan for the book. They mostly record place names. The manuscript is first recorded in the collection of Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700), after which it resided at the Jesuit Colegio Máximo de San Pedro y San Pablo in Mexico City before coming into the possession of the Italian collector Lorenzo Boturini Benaducci (1702-1751), after whom it is named.

Confiscated by Pedro Cebrián y Agustín (1687-1752), Count of Fuenclara and Viceroy of New Spain, the codex was housed in various repositories (Escribanía de Gobierno, Biblioteca de la Real y Pontificia Universidad de México, Convento de San Francisco, and the Ministerio de Relaciones Interiores y Exteriores) before moving to the Museo Nacional de México.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Codex Boturini": Tira de la Peregrinación facsimile edition, published by Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2021

Request Info / Price