Giovanni Sercambi's Chronicle of the History of Lucca, preserved in manuscript MS 107 at the Archivio di Stato di Lucca, is one of the most remarkable historical and artistic witnesses of late medieval Tuscany. Written between 1369 and 1423 by the Lucchese merchant, apothecary, and civic official Giovanni Sercambi, the chronicle offers a vast and vivid account of Lucca’s political, religious, and social life from 1164 to 1400. Conceived as both a patriotic tribute and a moral guide for citizens, the work embodies the civic pride and complex political consciousness of a city balancing between republican liberty and lordly rule.

The chronicle recounts a period of shifting alliances, economic revival, and spiritual tension. Through hundreds of pages and more than six hundred miniatures, Sercambi turned history into a living tapestry.

Giovanni Sercambi: The Citizen as Historian

Born around 1345 into a family of prosperous apothecaries, Giovanni Sercambi belonged to Lucca’s dynamic urban middle class. His social position offered him a unique vantage point: he was close enough to power to witness its intrigues, yet grounded enough to understand the pulse of ordinary citizens. Educated and politically engaged, Sercambi rose to hold important offices in the commune, eventually serving under Paolo Guinigi, the lord who ruled Lucca from 1400 to 1430.

His loyalty to the Guinigi regime has long divided scholars. Some saw him as a partisan propagandist; others, as a civic moralist who sought stability in times of chaos. Yet Sercambi’s Chronicle resist easy classification. They reveal a writer torn between nostalgia for republican liberty and faith in divine order; a man who understood history as both providence and human endeavor.

The Making of the Chronicle: Structure and Sources

MS 107 represents the first and most complete part of Sercambi’s Chronicle, covering the years 1164–1400. A second manuscript, preserved separately as Archivio Guinigi 266, continues the story to 1423. Together they form a monumental civic history of Lucca, blending chronicled events with moral reflections, short tales, and even allegorical fables.

Sercambi drew inspiration from earlier Tuscan and Latin sources, including Ptolemy of Lucca’s Annales, the Gesta Lucanorum, and the Fioretto di croniche degli imperatori. Yet his voice is unmistakably his own. He retold inherited narratives through the lens of experience, inserting eyewitness observations, local anecdotes, and vivid moral commentaries. He was both compiler and interpreter, transforming past chronicles into a coherent story about divine justice and civic destiny.

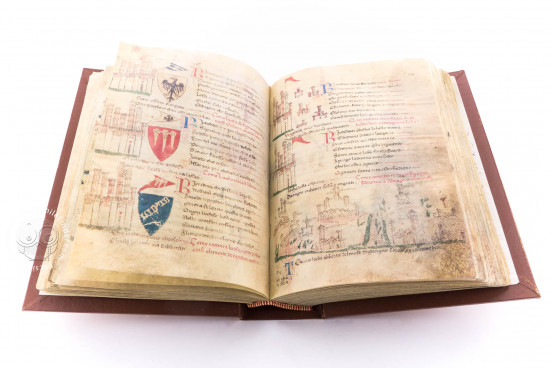

The result is a manuscript that feels almost cinematic. Each entry, however brief, is linked to a miniature that expands the narrative beyond words, inviting the reader to read the history through the images.

The Illuminations: Art as Historical Witness

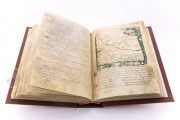

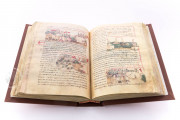

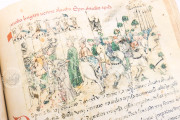

The visual program of MS 107 makes it one of the most lavishly illustrated civic chronicles of medieval Italy. Over six hundred miniatures accompany the text, offering an unbroken visual rhythm of battles, councils, festivals, and miracles. The anonymous artists, possibly trained in Lucca’s own workshops, followed Sercambi’s instructions closely, translating his vision into color and form.

The opening illumination sets the tone. At the top, Christ reigns in majesty, surrounded by Saints Peter, Paul, Martin, and Paolino, Lucca’s heavenly patrons. Below appear Pope Urban V and Emperor Charles IV, kneeling in harmony beneath the banners of their offices and of the city itself. It is a tableau of cosmic order, an image of the world as Sercambi wished it to be: Church, Empire, and Commune united under divine will.

Throughout the manuscript, the miniatures serve more than decorative ends. They interpret history, moralize events, and embed local identity within universal order. The scenes of public ceremonies, religious processions, and armed conflicts capture not only political drama but also civic ideals that defined Lucca’s self-image.

Freedom, Morality, and the Lucchese Spirit

At the heart of Sercambi’s chronicle lies an enduring theme: libertà lucchese, the freedom of Lucca. For him, freedom was not merely political independence but a moral state, a gift to be preserved through virtue and good governance. Even as he served under Paolo Guinigi’s lordship, Sercambi framed his narrative as a lesson in ethical citizenship.

He lamented the corruption of rulers, the fickleness of the crowd, and the temptations of greed, yet never abandoned hope in divine providence. His reflections on events such as the 1396 Battle of Nicopolis reveal a mind that understood history through both faith and economics: the defeat of Christian forces, he writes, brought “sorrow to our merchants of Lucca,” intertwining moral outrage with pragmatic concern.

This dual sensibility, moral and mercantile, makes Sercambi a quintessential figure of the early Renaissance city-state: pragmatic yet idealistic, devout yet analytical, rooted in local identity yet open to the wider world.

The Afterlife of MS 107

After Sercambi’s death from plague in 1424, his manuscripts entered civic custody. The first volume, MS 107, was seized from Paolo Guinigi’s library after his fall in 1430 and inventoried as Liber chronicarum Lucane civitatis factus per Iohannem Sercambi. It remained in the Palazzo Pubblico and was later transferred to the Archivio di Stato di Lucca, where it still rests today, remarkably well preserved.

We have 1 facsimile edition of the manuscript "Giovanni Sercambi's Chronicle of the History of Lucca MS 107": Cronica De Lucca De Giovanni Sercambi MS 107 facsimile edition, published by AyN Ediciones, 2006

Request Info / Price