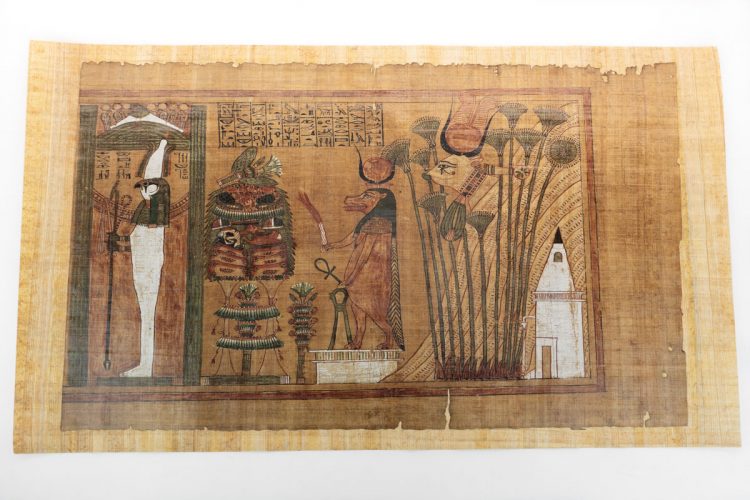

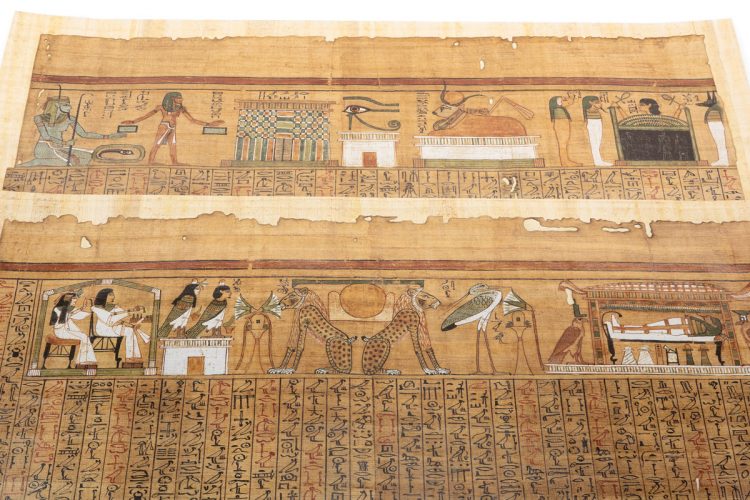

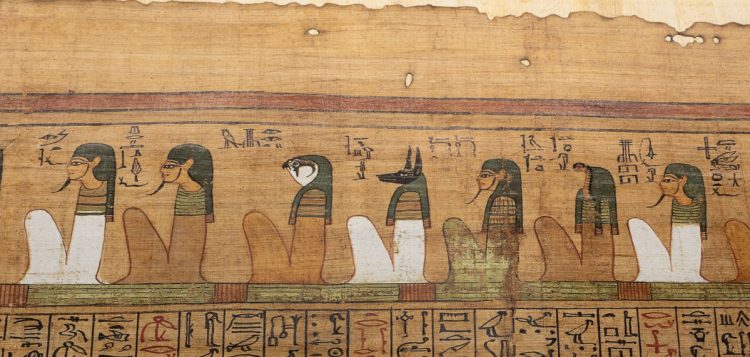

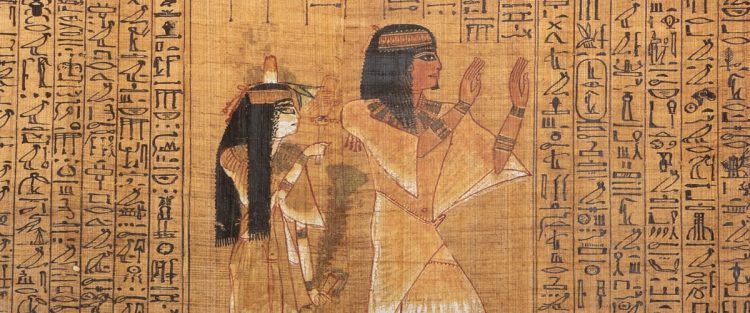

How challenging is it to produce a papyrus facsimile? In this interview, CM Editores tell us all about how they managed to replicate a two-millennia-old treasure that merges ancient Egyptian figurative art and afterlife beliefs: the Papyrus Ani.

Many precious facsimiles pass through our hands each week, but when we unwrapped CM Editores‘ replica of the Papyrus of Ani, our minds became flooded with questions on how it was produced. Directors Pedro Iribarnegarayand Daniel Díez were happy to answer all of them.

Giovanni: How did you come up with the idea of producing a facsimile of the Papyrus Ani? Did it stem from a passion or were you inspired by something in particular?

Daniel: We’ve always wanted to reproduce a book that was not just famous, but also surrounded by a certain amount of mystery, and the Papyrus Ani has it all: Egypt, life and death, art, history, and paintings worthy of the tombs of any powerful Egyptian pharaoh.

Giovanni: How did you obtain HD images of the Papyrus Ani?

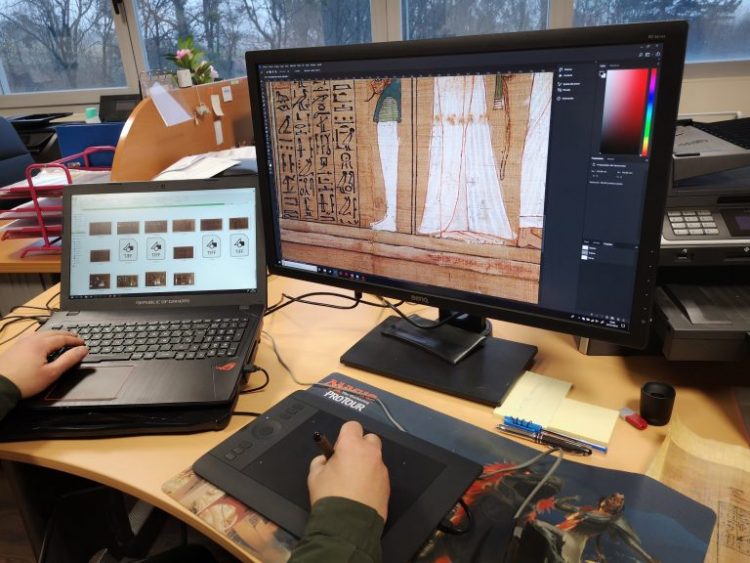

Pedro: By negotiating rights with the British Museum. They had a few 20×25 cm slides of the Papyrus which had been scanned with (now obsolete) mid-90s equipment, and in spite of their great quality they were not useful for our project. So we asked the museum staff to scan the original slides a second time with modern, first-class equipment (6400 ppp optical scanners), resulting in images that were 100 times better both in terms of size and quality.

Egypt is the only country in the world where papyrus is grown and processed the same way as it was 4000 years ago.

G: Which experts did you consult to obtain all information on the papyrus?

D: We consulted Ignacio Ares, an Egyptologist and journalist, probably Spain’s greatest expert on ancient Egypt, and Zahi Hawass, former Egyptian Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, a renowned archaeologist and Egyptologist, and possibly the world’s greatest expert on ancient Egypt. At the beginning of our project we also talked to another acclaimed Spanish Egyptologist, Jose Ramon Accino, who helped us but could not join the project due to other commitments. We also visited the Egyptian Museum in Turin, which holds another exemplar of the Book of the Dead, which is very long but lacks the magnificent scenes of the Papyrus Ani.

G: How and where did you find natural papyrus folios? Did you use special ones to print the facsimile?

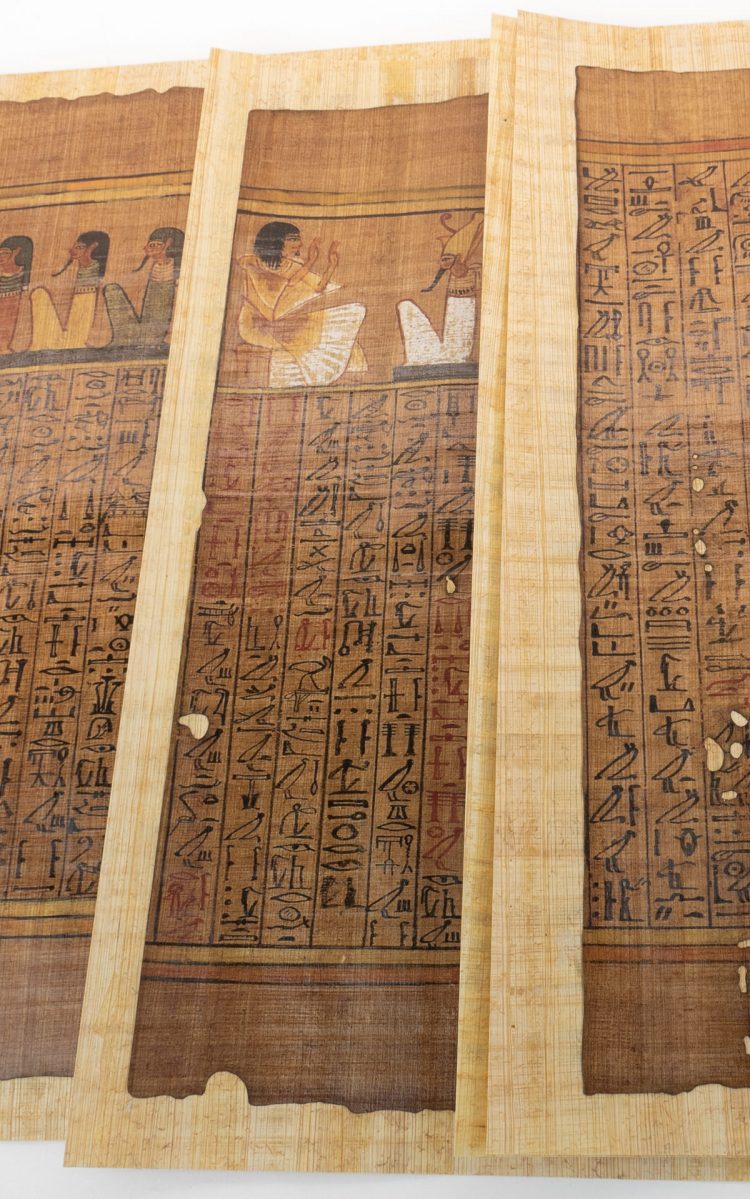

P: This was one of the most complicated processes, because being completely faithful to the original meant finding the original material, that is, papyrus. We are used to working with many different kinds of paper – most of which are Italian – and using a live support such as papyrus proved an even greater challenge. We sourced the papyrus directly from Egypt, since it is the only country in the world where the papyrus plant is grown and processed the same way as it was 4000 years ago as writing material. Our supplier manufactures them especially for us, because we need sheets that are more than twice as large as what is commonly produced.

G: What are the main phases of papyrus production and how long does it take to print on?

D: First of all, papyrus isn’t produced all year long. It is harvested in June on the banks of the Nile and its tributaries, so the number of facsimiles we are able to make depends on whether the harvest has been good or bad. Once enough papyrus sheets have been manufactured, they are sent to Spain, where we check them one by one and send them to the printing company. Here they are printed on with special ink and dried with ultraviolet rays to prevent the papyrus from absorbing ink.

Traditional cutters and milling machines tore apart the fiber of the papyrus because they are made for handling materials like metal and steel.

Next, we make holes into it using laser cutting to match the layout, tears, and scratches of the original document. Lasers can reproduce details as small as one thousandth of a millimeter (one micrometer). We usually produce 4-5 copies every 10 days, but if we consider the time our supplier in Cairo needs to make the sheets, the whole process can take up to 5 or 6 months.

G: Did you discover anything interesting or peculiar during the production?

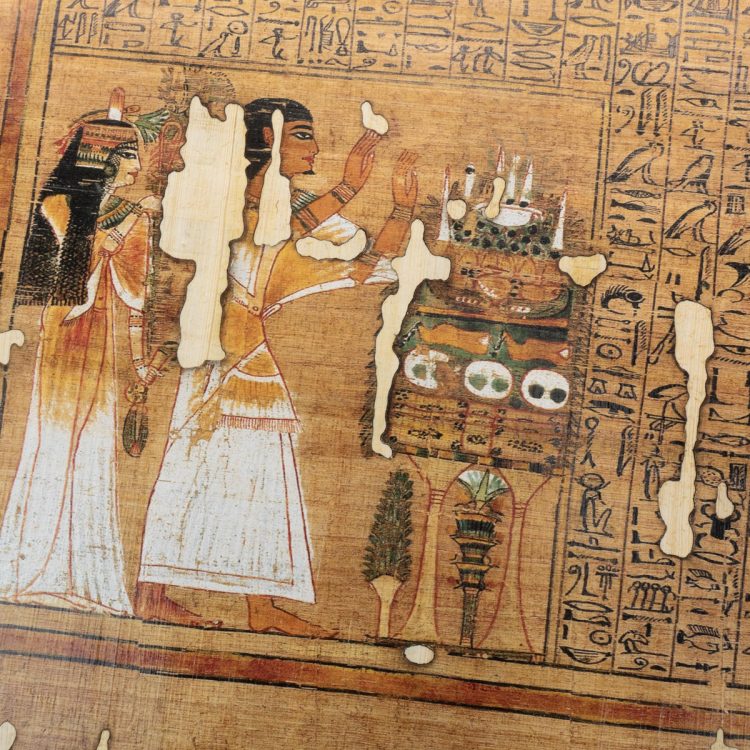

P: We didn’t expect that sourcing papyrus would be so difficult. Paper, although rare, is available right away or in a short amount of time because it is constantly being produced. But once all the papyrus sheets have been used, there are none left until the next shipment. A further challenge was reproducing the hue of the original papyrus background, which underwent changes because it has been kept rolled up for thousands of years.

G: Which steps proved the most difficult? Which part was the hardest to reproduce?

D: The hardest part was probably reproducing and punching the holes. When we tried doing it with traditional printing techniques the result was terrible, lacking in detail and very poorly defined. Traditional cutters and milling machines did not prove successful even after many tries, because they tore apart the fiber of the papyrus.

We needed to cut the papyrus in a way that would not impair its surface, and the only possible technique was laser. We had to buy laser equipment specifically for this job, as the ones that are commonly sold are too powerful because they are made for handling metal and steel. On the other hand, the Co2 machines, used for marking and engraving plates, were too small for papyruses of the size we use. So we had to find a manufacturer that sold a specific model for what we were doing, and after one year of searching, we finally found it.