When is the best time to plant seeds? What day of the month is it? When is Easter this year? With an upcoming facsimile by Quaternio Verlag, 21st-century readers can find answers to all these questions — the medieval way.

Stuck at home during the coronavirus lockdown, we all put on gardening gloves and dug the ground in our gardens to plant zucchini, cherry tomatoes, and lettuce.

Just like millions of others around the globe, we rediscovered a pleasure modern society has almost taken away from us — a pleasure that in the Middle Ages was a matter of life and death.

So, with burnt foreheads and soil under our nails, we wondered: what is the right time to plant radish? When is the best moment to water strawberries?

We are lucky to find answers just by typing the words into a search engine, but how did people find this invaluable information before the age of the internet — and even before the invention of the printing press?

In medieval societies, the answers to such questions — and many more — lay in booklets as concise as they were valuable, often bound together with other texts, mainly Psalters. They were called almanacs, and they always contained a calendar.

So if you are ready for the challenge, try to do without modern calendars and web searches for one day — and dive into the medieval world with us!

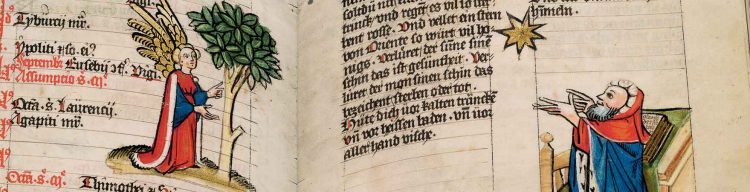

For our little time travel, we will be looking at images from a precious medieval almanac preserved in Strasbourg’s National University Library with the shelfmark Ms. 7.141, which Quaternio Verlag Luzern is working on publishing in facsimile.

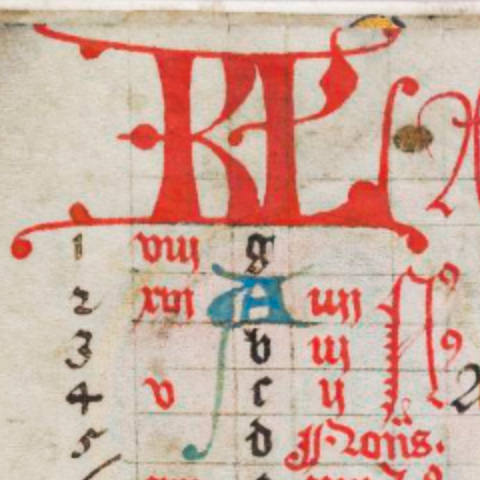

Calendae, or the first day of the month

At the beginning of each calendar month were always the initials KL, which stand for calendae, the first day of the Roman month.

The ancient Roman system of kalends is what gave the name to modern calendars.

Unlike us, and following the Roman tradition, medieval people didn’t number days sequentially, although their months were also made up of 30 or 31 days.

And can you see those letters in the third column from the left, running from a to g? They were called Dominical Letters, because people used them to determine the days of the week starting from Sunday — each year had its Sunday letter.

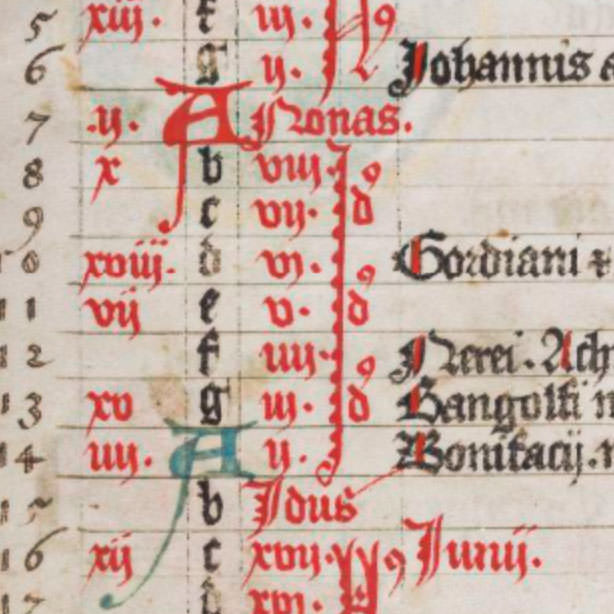

How many days before?

The medieval calendar was divided into three parts based on kalends, nones, and ides.

Nones came either on the fifth or seventh day of the month, and ides fell eight days after nones.

In the image on the right, nones falls on the seventh day, and ides on the fifteenth day, eight days later.

By counting how many days before the kalends, nones, and ides, people could determine the day of the month.

So, if in the Middle Ages someone asked: “what day is today?” The answer would not be “the tenth day of the month” but rather something like “the fifth day before ides”.

Health advice for animals and humans

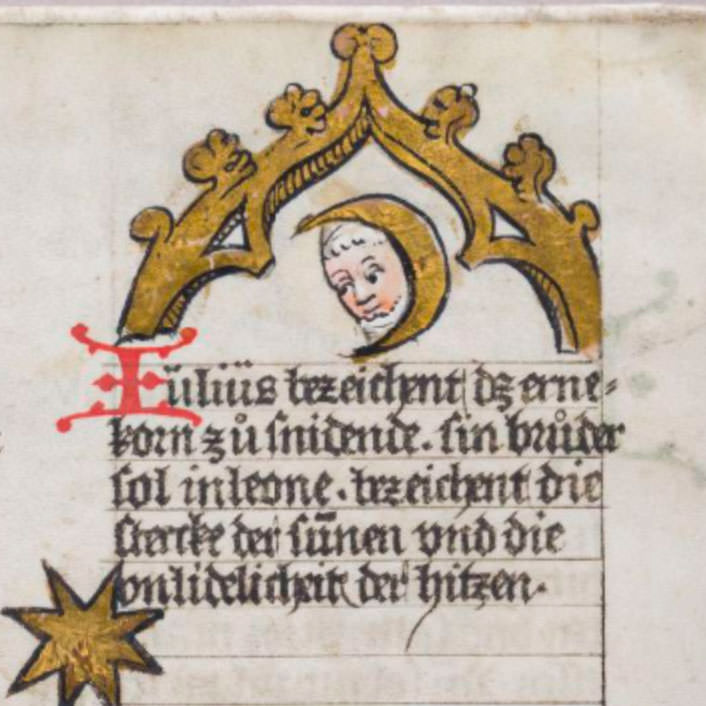

Determining the day of the month was only one of many purposes of medieval calendars — by knowing the position of the moon and stars, peasants could find out the best time to plow, geld animals, and even how to cure them with a myriad remedies, like placing water pepper under a horse’s saddle.

The best almanacs also contained rigorous health and nutrition advice for humans: in the month of May, everyone should drink goat’s milk with herbs in the morning.

Based on medieval ideas, human character and health were determined by cosmic forces — information about the cosmos was therefore essential to treat or prevent bad health.

The labors of the month

Medieval calendars didn’t just provide useful information, they also contained beautiful images showing the occupations of the month, illustrating what people would do during a particular time of the year.

Activities included scenes of labor such as harvesting, sowing, or threshing, depending on the area where the manuscript was made — calendars in northern Europe showed different activities and plants from the ones made in southern Europe.

The Medical and Astrological Almanac, made in the mid-15th century in the area between southern Germany and France, shows fairly traditional images, like a man warming his feet by the fire in February, a girl picking flowers in April, a boy enjoying hawking in May, a couple making wine in October, a man gathering acorns for hogs in November and slaughtering a pig in December.

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

These wonderful images come from a 15th-century calendar to be published in facsimile by Quaternio Verlag Luzern in autumn 2020.

NEW WEEKLY VIDEOS

Find our more about Herbolarium et materia medica (Lucca, Biblioteca Statale di Lucca) on our website!

Find our more about the Codex Legum Langobardorum (Cava de’ Tirreni, Biblioteca Statale del Monumento Nazionale della Badia) on our website!