Explore with Liz Teviotdale the mesmerizing world of three closely related illuminated Apocalypse manuscripts from 14th century England. Uniting the Latin with an Anglo-Norman translation, commentary, and striking imagery, these manuscripts offer a captivating glimpse into Saint John’s apocalyptic visions.

Three closely related illuminated Apocalypse manuscripts were produced in England—probably in London—in the second quarter of the fourteenth century: the Toulouse Apocalypse, an Apocalypse in the British Library (London, British Library, MS Add. 18633), and the Corpus Apocalypse in Cambridge. Their primary texts and the style and iconography of their imagery are very similar, but none is a direct copy of one of the others.

What sets these three manuscripts apart from the many other illuminated English Apocalypse manuscripts is their bringing together of the Latin text of the Apocalypse from the Christian Bible, a translation of the biblical text into Anglo-Norman (the French spoken in England at the time), and a prose commentary in Anglo-Norman.

A Glimpse into Process

The Corpus Apocalypse—probably a bit later than the other two—is the most sumptuous, but the manuscript now in Toulouse is the most interesting for what it reveals about the development of this particular type of illuminated Apocalypse.

Episodic Quality

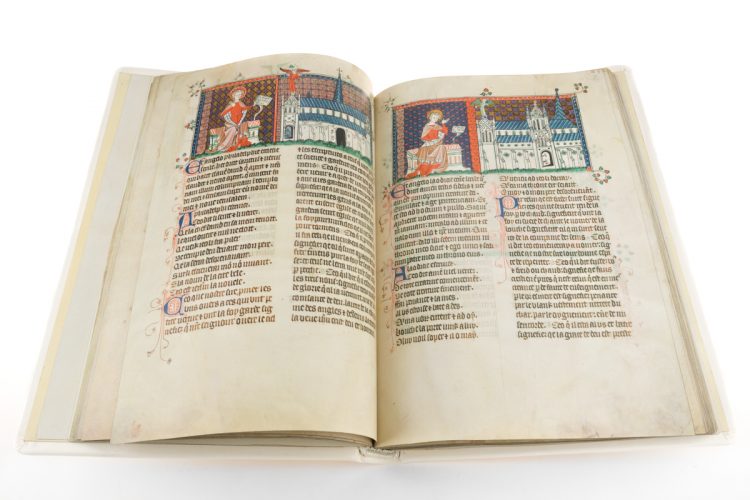

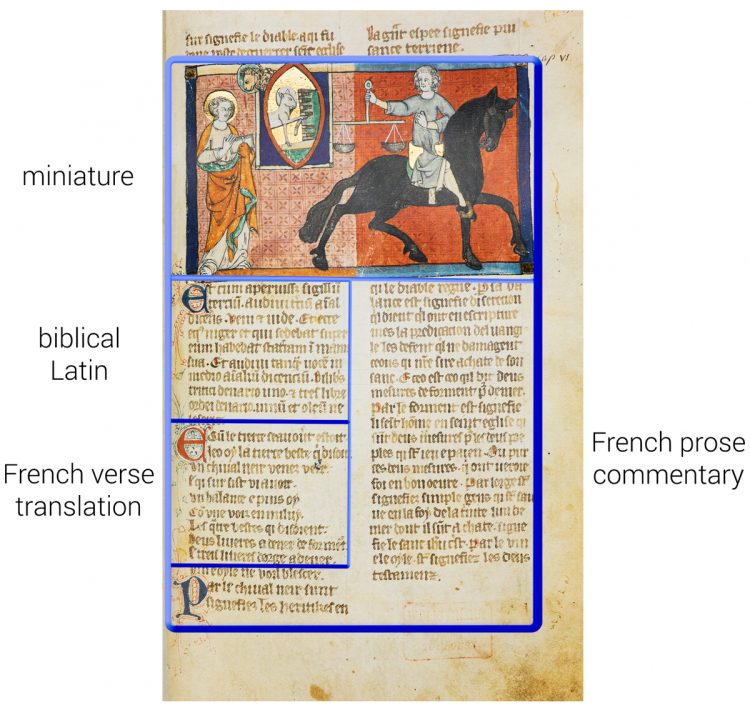

In all three manuscripts, Saint John the Divine’s vision of the events leading to the end of time is detailed in more than a hundred episodes. First comes an image, customarily a framed rectangular miniature extending across the two columns of text. Three snippets of text related to that image follow: the biblical text in Latin, then a translation of the Latin into French verse, and then commentary on the episode in French prose. A pen-flourished initial introduces each text.

An Orderly Arrangement

The scribe of the Toulouse codex endeavored to fit these three bits of text into columns of equal length, but he was only sometimes successful. When not, an adjacent miniature might be of irregular shape to fill the space. In the other two manuscripts, there are far fewer irregularities, suggesting that the scribe of the Toulouse manuscript first combined these texts.

Taking Advantage of Available Space

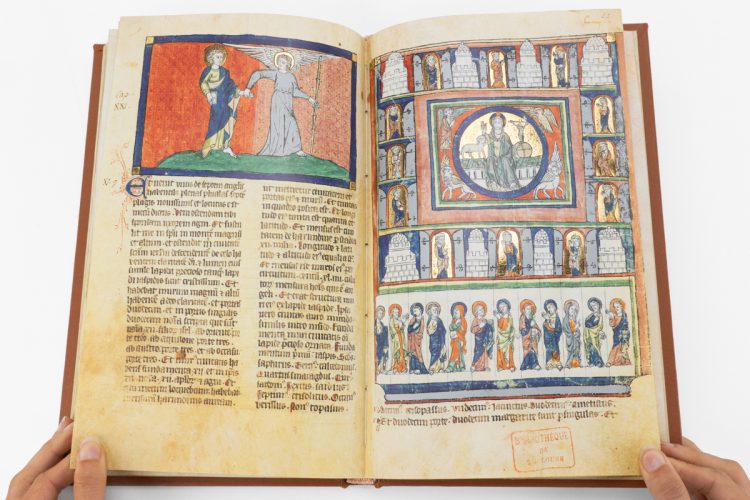

In the miniature of the pouring out of the seventh vessel (Apocalypse 16:17), the illuminator of the Toulouse Apocalypse takes advantage of the taller right half of the miniature to make the representation of Christ in Majesty very imposing, entirely in keeping with what it represents: “a great voice out of the temple from the throne saying ‘It is done’.” In the other two manuscripts, the scene is in a rectangular miniature with Christ in Majesty squeezed into the upper right corner.

Words Made Physical

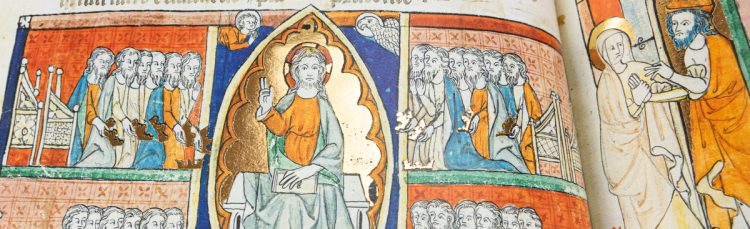

Although not unique to this group of Apocalypse manuscripts, a noteworthy feature is the transformation of figured language into image. For example, in all three, when a voice “like a trumpet” addresses John (Apocalypse 4:1), the miniature depicts an angel blowing a trumpet over the head of the seated saint.

A surprising example (at Apocalypse 10:1), found in the Toulouse and London codices, is the transformation of the great angel’s feet “like pillars of fire” into stone pillars. The angel’s feet are more conventionally rendered as flames in the Corpus Apocalypse.

Images Transcend Text

The manuscripts are so densely illustrated that, in at least one instance, a pair of miniatures illustrating separate events can be seen as a composite image in the Toulouse and London manuscripts.

Near the climax of the biblical narrative, an angel with a golden measuring rod appears to John (Apocalypse 21:15), and a miniature is devoted to the subject. The Heavenly Jerusalem is pictured on the facing page. By including the detail of the angel holding John’s wrist and leading him, the illuminator turns the two images into a composite scene of the angel urging John forward to experience his vision of the celestial city.

As captivating as the details of the imagery are, there is no mistaking the disturbing nature of the multi-headed beasts, natural disasters, and mischievous demons described in Saint John’s vision and represented in the manuscripts.