What do the Holy Trinity, the Desert Fathers, and a terrified man fleeing from a giant snail have in common? Surprisingly, they are all masterfully depicted within the curious yet captivating manuscript known as the Rothschild Canticles. But what connects this peculiar imagery, along with several other profane illustrations found in the margins, to the sacred themes of the text and its full-page theological illuminations? Continue reading, and join us in unraveling the mystery.

Rich in striking and unusual imagery, the Rothschild Canticles manuscript is an extensively illuminated compendium of Christian texts and pictures that invite prolonged and repeated contemplation. It was illuminated around 1300 in northern France at the Benedictine Abbey of St. Winnoc in Bergues, presumably for a nun or canoness, and provides unique insight into her spiritual life. The manuscript comprises two parts of nearly equal length.

The First Section: A Journey Towards Initiation Through Words and Unconventional Imagery

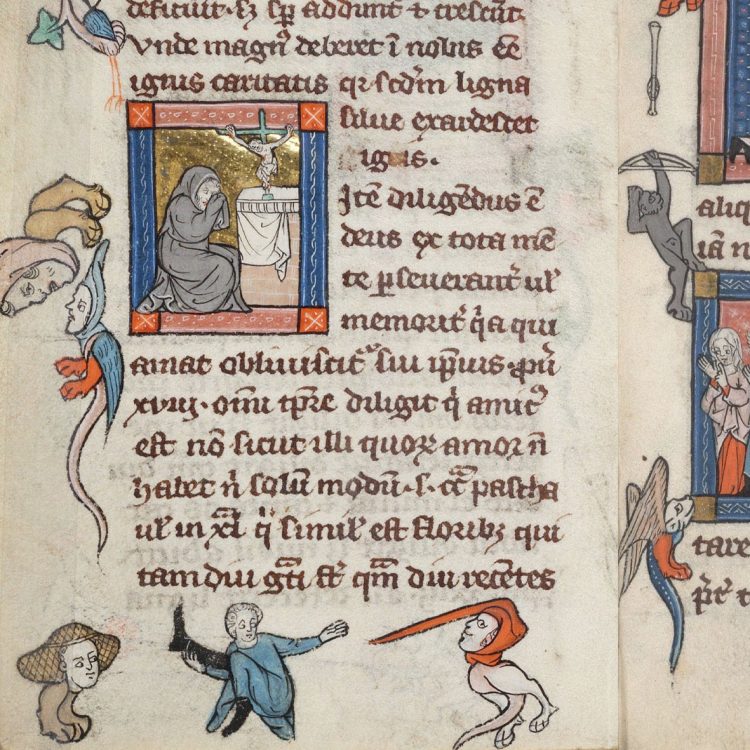

Following a series of prefatory miniatures, the first part presents a perfect balance of word and image. Indeed, each unit occupies two facing pages: text dominates the left-hand page, whereas a full-page miniature can be found on the right. According to the scholar Jeffrey F. Hamburger, this section – which comprises short excerpts from biblical, liturgical, and dogmatic texts, as well as aphorisms and prayers – “invites the devotee to pass from meditation (reading) to contemplation (seeing, here defined in visionary terms)”.

In this section, both the pleasures of Paradise and the allegories of the Song of Songs are considered. However, the mystery of the Trinity is the true central subject: here, the triune God, both one and three, is visualized in unprecedented ways. The profusion of miniatures of the Trinity—nearly twenty surviving—drives home the concept that the Godhead, even if repeatedly presented in pictorial form, is unknowable. Each artistic rendering can only hint at the mystery.

The Second Section: Enhancing the Readers’ Experience with Engaging Illustrations

While the initial portion of the Rothschild Canticles provides a structured introduction to contemplative living, as noted by Hamburger, the second section presents “a more fluid collection of instructive materials designed to enhance the reader’s experience”. This section appears more conventional in its presentation, with each section introduced by a small miniature or historiated initial. The margins of this portion teem with animals and fantastic creatures that interact playfully.

Another series of full-page miniatures was a belated addition. They are scenes from the lives of early Christian hermits of the Egyptian desert. In contrast to the complex theology of most of the manuscript, these are more straightforward narrative scenes, albeit expertly drawn and painted. We may be able to glimpse the manuscript’s original owner among the prefatory miniatures of the seven liberal arts [fol. 7r, bottom left].

Curious and Uncommon Drolleries on the Margins

Binding the entire manuscript together – and in seeming opposition to its main subject matter – is a droll set of images crowding its margins. These miniatures depict various creatures: monkeys, dogs, birds, swordsmen and even disembodied heads, most partaking in odd activities. On one page, for example, a man carrying a pen twice his size flees from a giant snail [fol. 187r]. This and other similar images seem to represent the struggle of writing and reading, as well as the search for significance.

The apparent randomness of the marginal miniatures could lead the reader to question their purpose. Nevertheless, according to Hamburger, “not only does [this imagery] embrace human nature… it also points towards a happy ending in so far as the soul’s salvation rescues it from the degradation of death and damnation, to which the outright violence of the marginal imagery repeatedly alludes.”

In conclusion, the Rothschild Canticles’ manuscript leads the reader on a journey mapped by wonderful and often surprising miniatures, allowing her to ponder and contemplate Christian mysteries. Moreover, it stands out as one of later Middle Ages’ most richly illustrated manuscripts, as well as one of the most unique, given that only a few of its images adhere to traditional iconography.

Jeffrey Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300, Yale University Press, 1990.