The Liber Abaci introduced to the Western world the numerals we use today, along with the sequence that led to the Golden Ratio, which lies at the heart of some of the greatest works of art ever created. Explore how mathematics traveled from India to Italy and became the universal language of beauty.

Why This Manuscript Matters

- First systematic European introduction of Arabic numerals and zero

- Birthplace of the Fibonacci sequence, linking mathematics and beauty

- Foundation for Renaissance theories of proportion and perspective

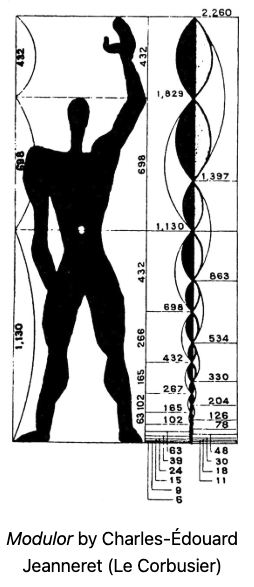

- Influenced Leonardo da Vinci, Luca Pacioli, Gaudí, and Le Corbusier’s Modulor

- Preserved in Florence, cradle of Renaissance intellectual culture

The Global Story of the Liber Abaci: When Numbers Became Culture

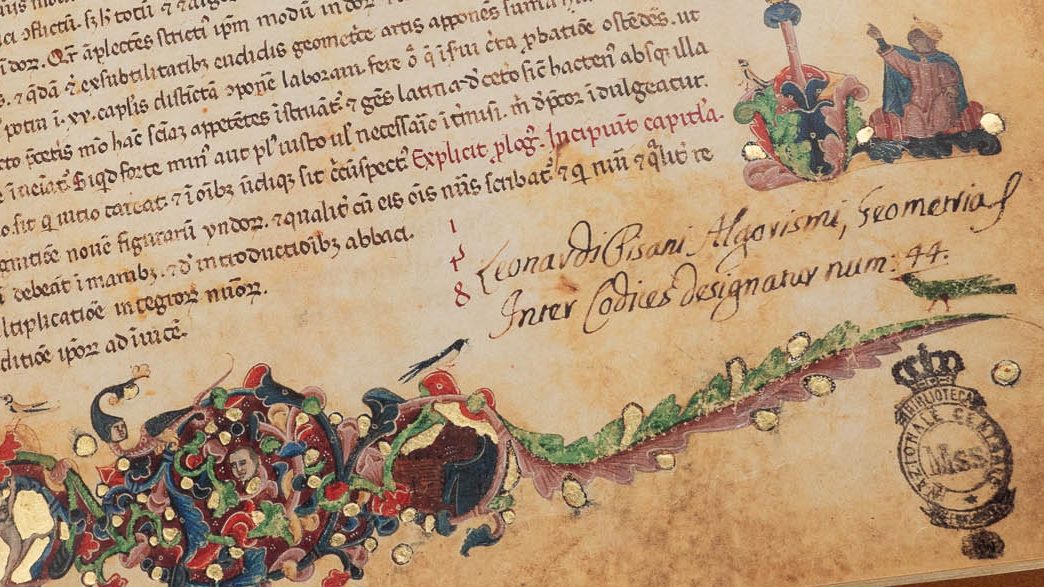

Few works have reshaped human knowledge as profoundly as Leonardo Fibonacci’s Liber Abaci. Written in 1202 and revised in 1228, this Tuscan masterpiece introduced Arabic numerals, zero, and positional notation to Europe—laying the foundation for modern mathematics and altering the way the West measures, calculates, and envisions order.

Preserved today in Florence (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Conv. Soppr. C.1.2616), the manuscript stands at the crossroads of global intellectual exchange: from India’s mathematical innovations, through the Arabic scholarship of North Africa, to the bustling mercantile culture of Pisa and Florence. The Liber Abaci embodies the story of how knowledge travels—and how it transforms the world.

From India to North Africa to Europe: The Journey of Numbers

Long before the Renaissance, Indian mathematicians developed the decimal system and the concept of zero. These ideas were refined by Arab scholars and carried westward across the Mediterranean.

Fibonacci encountered this new numerical language as a young man in Béjaïa (modern Algeria), where his merchant father worked. In the Liber Abaci, he introduced Europe to Hindu–Arabic numerals, demonstrating their superiority over Roman numerals through elegant algorithms, lucid examples, and real-world applications.

This moment—encoded on parchment—marks the birth of Europe’s modern mathematics.

The Fibonacci Sequence and the Birth of Beauty

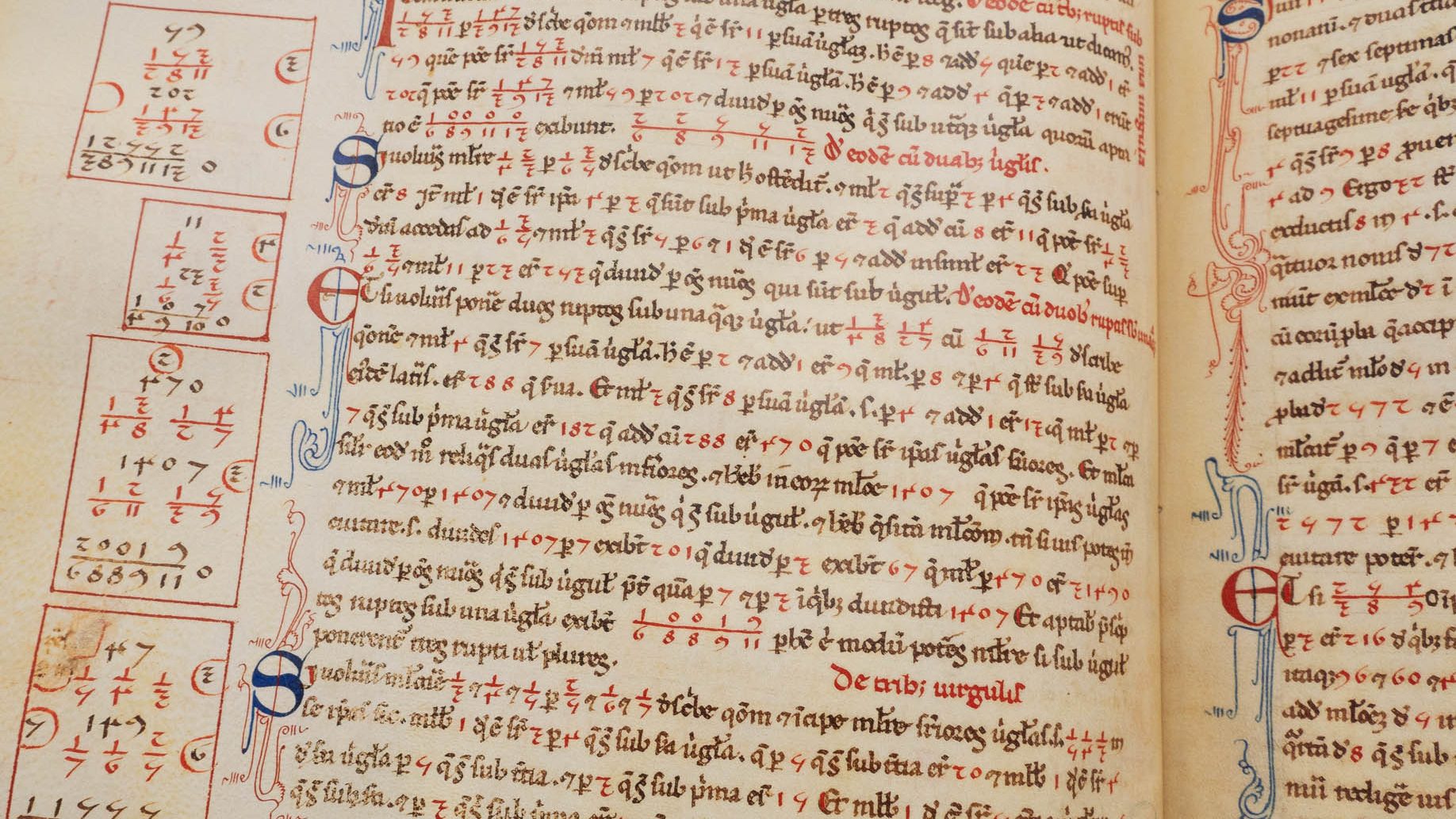

Among the treatise’s many problems appears a seemingly playful question about rabbit reproduction. Hidden within it is the now-iconic Fibonacci sequence, the Series defined by adding each term to the one before it (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13…).

This sequence, simple yet generative, became a key to understanding:

- natural spirals

- branching growth

- botanical patterning

- proportional harmony

Its ratios converge toward the celebrated Golden ratio, a proportion central to Renaissance aesthetic theory and later artistic experimentation. What originated in a practical calculation exercise evolved into a universal pattern shaping both nature and design.

From Leonardo Fibonacci to Leonardo da Vinci: Mathematics as Art

Centuries later, the Fibonacci sequence permeated the artistic imagination. The Golden ratio guided Leonardo da Vinci in his studies of perspective, anatomy, and visual balance—from the Vitruvian Man to the composition of The Last Supper.

Its influence continued far beyond the Renaissance. The same proportional logic resurfaces in Le Corbusier’s Modulor (1948), where the architect developed a modern system of harmonic measurement grounded in the Fibonacci Series and the Golden ratio. From classical painting to twentieth-century architecture, this mathematical language shaped the curves, grids, and spatial rhythms of modern design.

It also echoes in Gaudí’s organic forms and in contemporary explorations of geometric beauty across photography, typography, and digital aesthetics. Through these many afterlives, the Liber Abaci becomes a bridge between mathematics, nature, and art—a dialogue that continues across centuries.

Rhythms apparent to the eye and clear in their relations with one another. And these rhythms are at the very root of human activities. They resound in man by an organic inevitability, the same fine inevitability which causes the tracing out of the Golden Section…

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier)

The Florence Manuscript and the Legacy of a Tuscan Genius

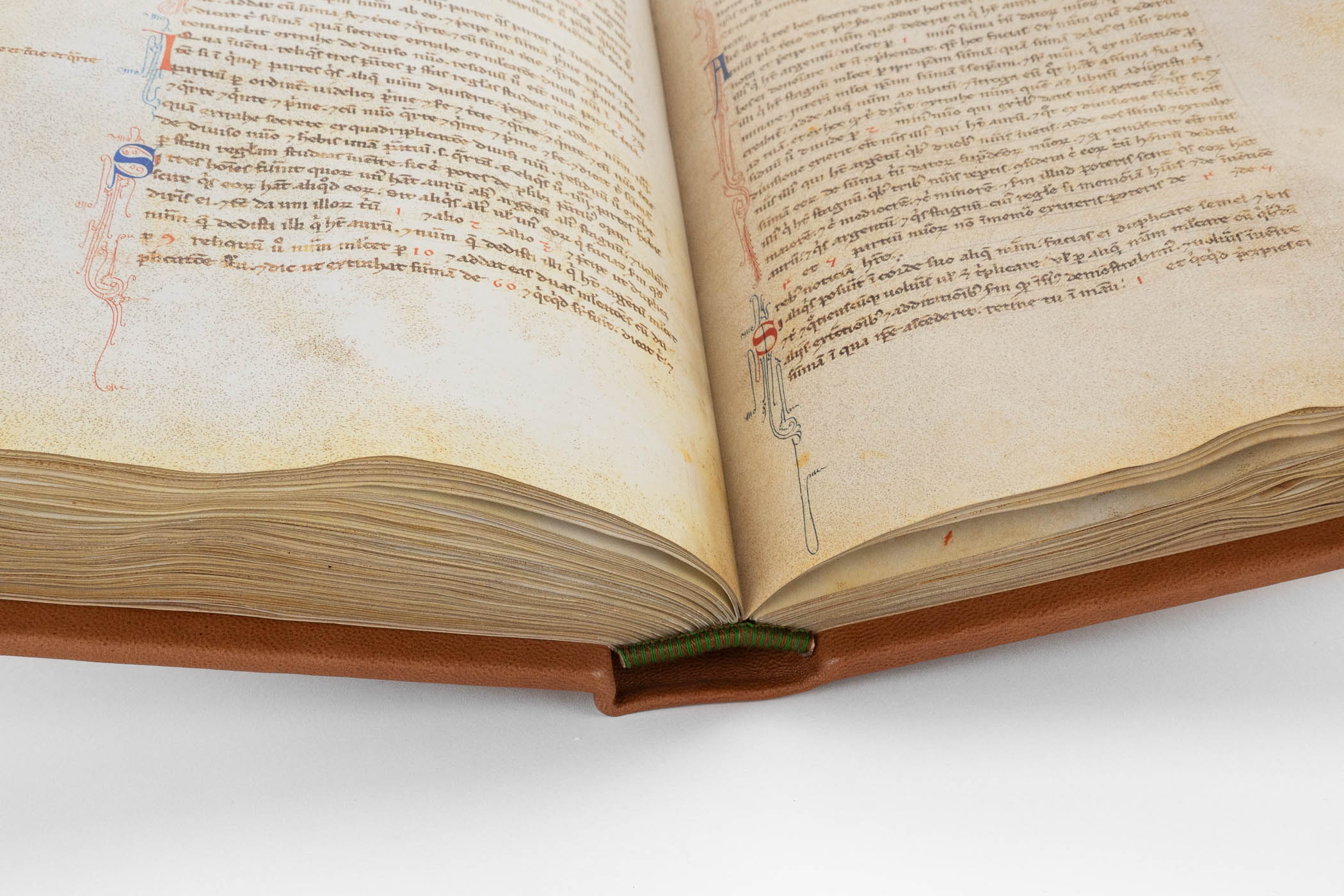

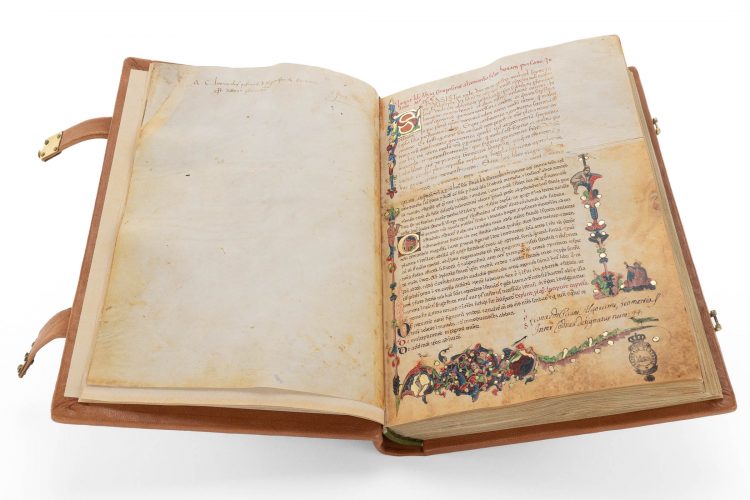

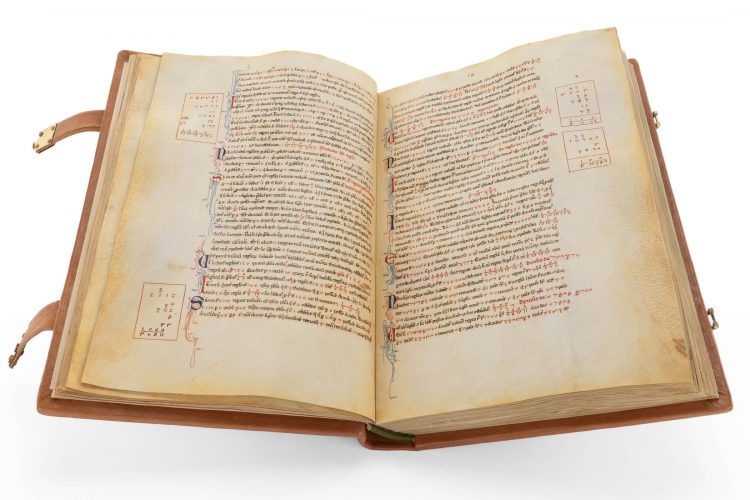

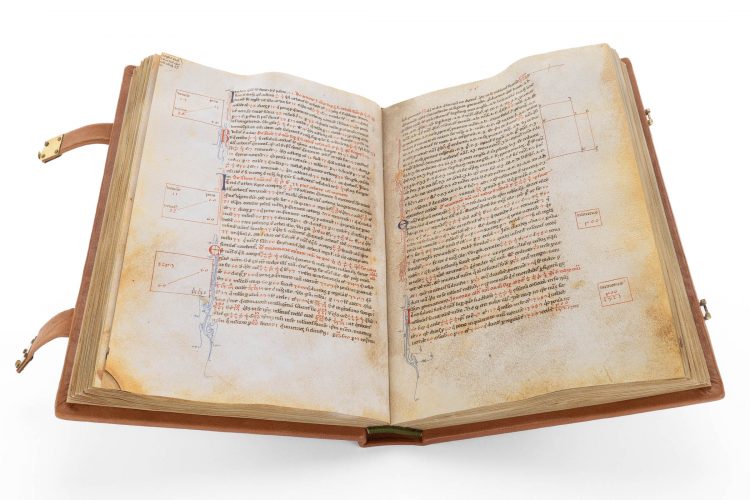

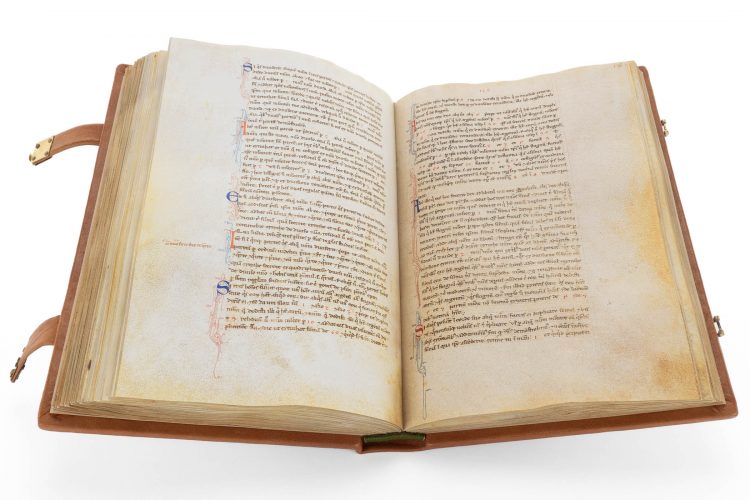

The Florentine manuscript of the Liber Abaci—a fourteenth-century parchment codex of 213 folios—is the fullest surviving witness of Fibonacci’s revolutionary vision. Its clear Gothic Rotunda script and systematic layout reveal a book designed for teaching and use, not for display.

In 1857, the scholar Baldassarre Boncompagni used this very manuscript to produce the editio princeps that finally introduced the Liber Abaci to modern scholarship. Today, the codex remains a cornerstone of mathematical history, preserving the moment when Europe embraced a new way of thinking about number, proportion, and scientific order.

Visit and Discover

The Liber Abaci is preserved in Florence, the city where mathematics, commerce, and art first merged.

Through the facsimile edition, students and collectors can experience the moment when numbers became a universal language — a bridge from India to Italy, from calculation to creation.

Secure your Copy of the Liber Abaci Facsimile

€ 2,584

Full-size color reproduction by Imago (2025)

Limited Edition: 221 copies

Learn more or request details at:

FacsimileFinder.com – Liber Abaci Fibonacci

FAQ: The Liber Abaci and Fibonacci

The Latin title Liber Abaci literally means “Book of the Calculation.” Although sometimes translated as “Book of the Abacus,” it focuses on arithmetic using the new numerical system, not the physical abacus.

The sequence predates Fibonacci and appeared in Indian mathematics. Fibonacci popularized it in Europe through his Liber Abaci, including the famous rabbit problem.

He is best known for introducing Hindu–Arabic numerals and decimal positional notation to Europe, and for the sequence that later became known as the Fibonacci sequence.

Yes. After his lifetime, his works were little known, and his influence faded until renewed interest in the 19th century.

Yes. Leonardo of Pisa (c. 1170–c. 1250) is nicknamed Fibonacci, meaning “son of Bonaccio.”

Each number is the sum of the two preceding ones: F₀ = 0, F₁ = 1, then 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc. A full list of the first 100 numbers can be generated using this rule.

It approximates the Golden ratio, the limit of the ratio of consecutive Fibonacci numbers. It appears widely in proportion theory, art, architecture, and nature.

From the prologue of Liber Abaci: “I wish the Latin race may in future not be found lacking in mathematical knowledge.”

No. While some natural spirals approximate the Golden ratio, the Milky Way’s arms follow more complex dynamics and are not exact Fibonacci spirals.

There is no highest Fibonacci number; the sequence continues indefinitely, with each term the sum of the previous two.

Fibonacci Day is celebrated on November 23 each year. The date 11/23 corresponds to the first four numbers of the Fibonacci sequence: 1, 1, 2, 3. It’s an informal celebration of Fibonacci, the sequence, and mathematical curiosity.