When the Duke of Modena, Borso d’Este, commissioned a lavish, two-volume bible to be illuminated by the best artists of his age, he had a specific political purpose in mind. Scroll down to see the video!

On a spring day in 1471, Borso d’Este traveled south across the Italian Po valley, where he had ruled as first Duke of Modena for almost two decades. His destination was St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, where Pope Paul II was set to make him Duke of Ferrara, transferring the territory from the Holy Roman Empire to the Papal States.

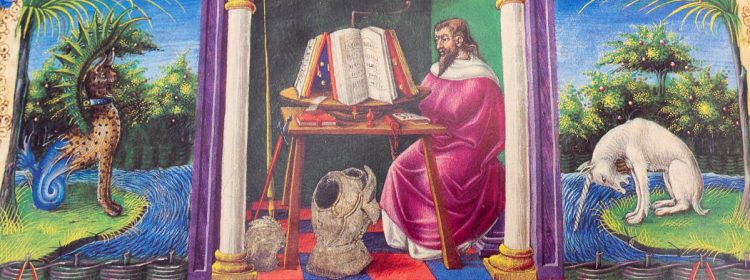

Among the objects Borso carried on his journey was one of the most exquisite Bibles of the Italian Renaissance. Its countless miniatures, enriched by floral decorations and golden frames, were the work of the most prominent illuminators of the region, such as Taddeo Crivelli and Girolamo da Cremona.

Borso d’Este had proved himself a patron of the arts by supporting the Ferrara school of painters, yet his aim was more pragmatic than poetic. The Holy Book he meant to show to the Pope was rich in symbols that had little to do with Christian faith and a lot to do with politics. By commissioning the Bible in 1455, the powerful Duke meant to prove his value as a ruler.

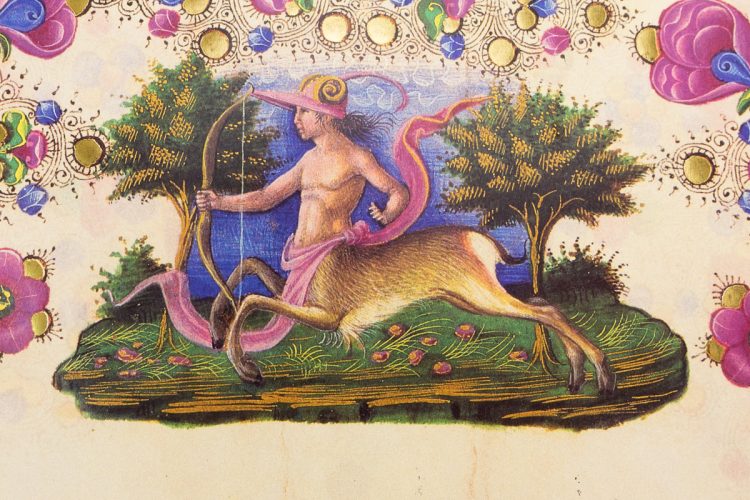

Centaurs may be the symbols of passion, excess, or adultery, and their peculiar hats and clothes recall the drolleries of Gothic manuscripts.

Earth, Water, Air, and Political Power

Among Borso’s achievements were the peace and prosperity he had brought to his fiefs, most notably through the land reclamation in the Polesine area that had allowed the city of Ferrara to prosper and expand its territory.

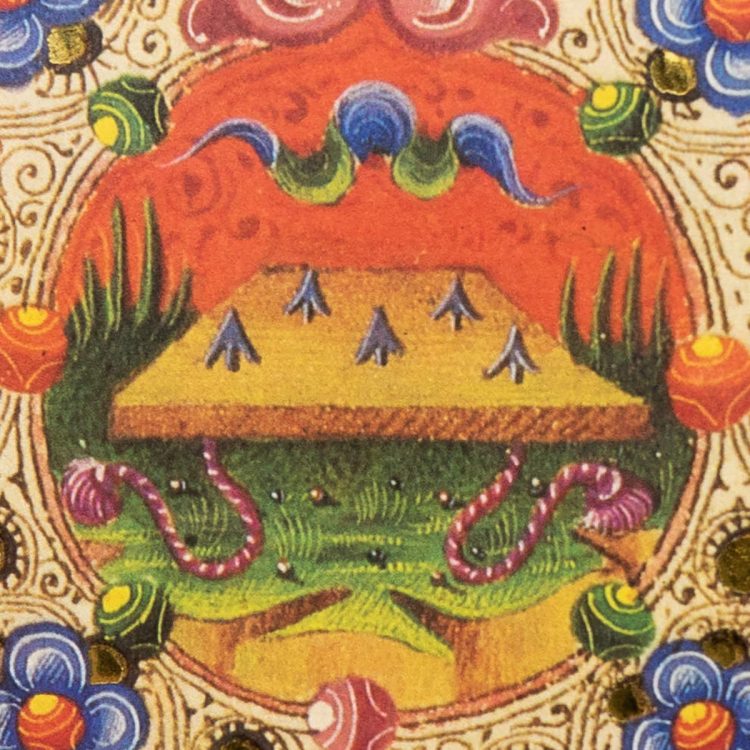

The Duke’s agricultural reforms were celebrated in many of the Bible’s medallions, with objects such as the chiodara, a wooden board with nails used as a harrow, and the paraduro, an embankment made of a wooden fence and a pumpkin that was used as a water gauge. The motto fido, written above the fence, expresses the trust in God and humankind.

Other medallions refer to economic activities that were popular in 15th-century Ferrara: the drinking trough (beveraduro or columbarolo) presumably represents pigeon breeding, while the fire pit may be an allusion to the glass workshop where many everyday objects were produced during Borso d’Este’s reign.

But these four objects may also conceal a more enigmatic meaning, namely Renaissance princes’ attempt to gain control over nature and mold the four elements: earth (the harrow), water (the embankment), air (the drinking trough), and fire (the fire pit). Borso d’Este even had these objects sculpted on the pillars of the Ferrara Charterhouse and embroidered onto his clothes.

A Bestiary or a Bible?

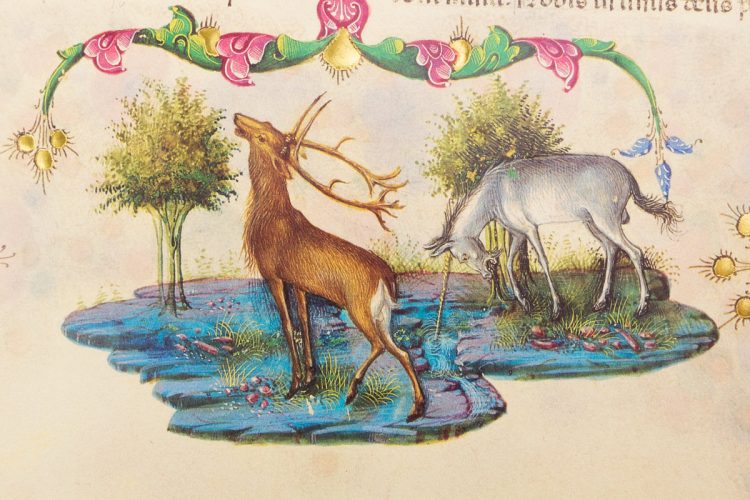

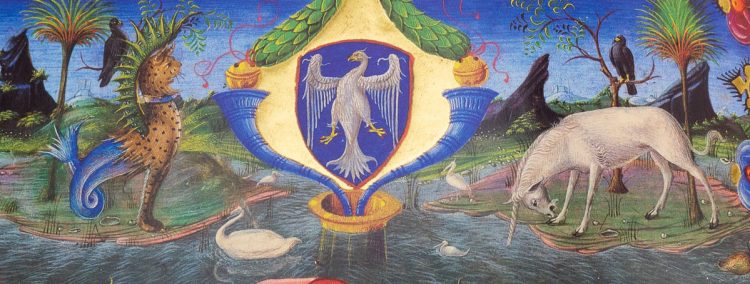

One of the Duke’s favorite pastimes was hunting, which sometimes distracted him from important political obligations. He owned a vast collection of wild animals, many of which are represented in his Bible and hold particular symbolic meanings: the peacock stands for immortality, the eagle for resurrection, and the dog for loyalty, while the deer represents humankind’s longing for God.

Imaginary animals also played a role in affirming Borso d’Este’s rulership: the unicorn, which is often seen dipping its horn in water to symbolically purify it, may refer to the Duke’s land reclamation or to his ability to free his people of troubles and concerns by safeguarding peace.

The unicorn’s virtues were probably attributed to the worbas, a lynx with wings like a gryphon and a tail like a mermaid, whose name probably derives from the ancient German worwaerts and translates as “going forward”, thus symbolizing Borso d’Este’s strong will towards development.

Centuries later, it is impossible to assess to what extent the manuscript contributed to his 1471 appointment as Duke of Ferrara, but one thing is for sure: the Bible of Borso d’Este counts as one of the most intricate and astonishing illuminated bibles crafted during the Italian Renaissance.

This article is based on an essay by Federica Toniolo. The essay is contained in the commentary to the facsimile edition of the Bible of Borso d’Este, published in 1997 by Franco Cosimo Panini.